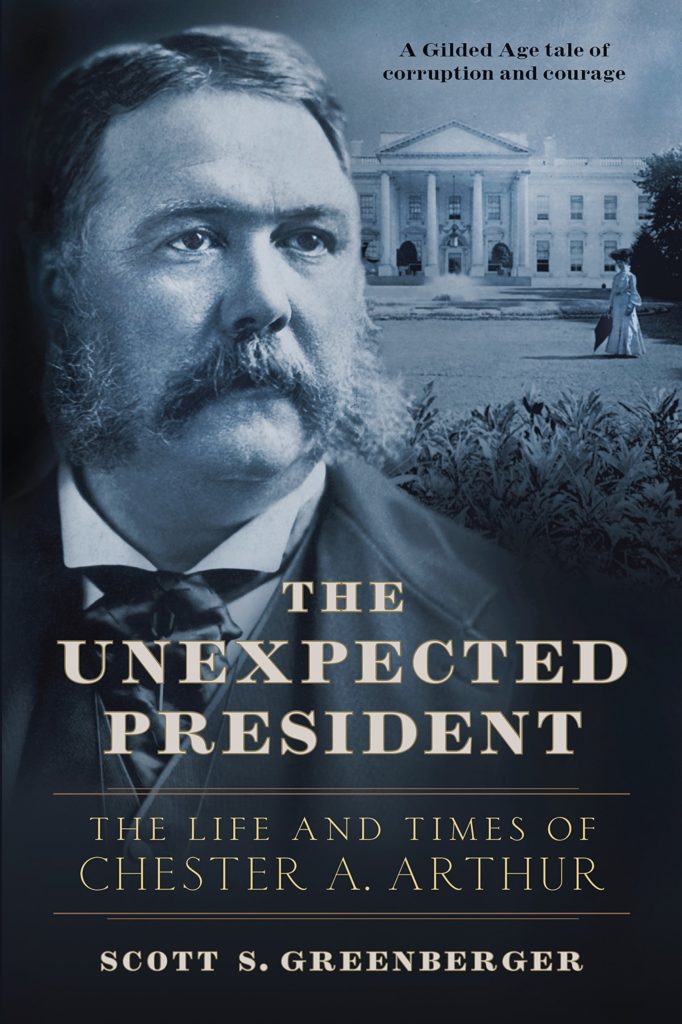

The Unexpected President

The Unexpected President is an aptly named biography of Chester A. Arthur. Â Author Scott S. Greenberger does an excellent job depicting the character of the 21st President of the United States.

The Unexpected President is an aptly named biography of Chester A. Arthur. Â Author Scott S. Greenberger does an excellent job depicting the character of the 21st President of the United States.

The oft-used subtitle, The Life and Times of …, is also very fitting.  Greenberger gives the reader a clear picture of what life was like in New York in the mid 19th century and highlights several of his subject’s contemporaries in telling Arthur’s story.

In fact, the book is worth reading for the side stories the author weaves throughout his narrative. He begins by providing a picture of the United States during Arthur’s youth. Arthur’s father was a strict, unbending, Presbyterian minister, who preached fiery sermons proclaiming the abolition of slavery at a time when the issue was not settled, even in the North. This was 3 decades before the Civil War would end the “peculiar institutionâ€. In the 1830’s, anti-Abolitionist riots were common, and Arthur’s family witnessed them first-hand.

Greenberger leaves the reader with an impression of Chester’s father as a man as unyielding in his strictures on morality to his own family as he was on the rectitude of his position on slavery. So it isn’t surprising that the young Chester became enamored with the freedom  and opportunities for decadence he found in New York.

This is not to say that Arthur succumbed immediately to a dissipated lifestyle.  For one thing, he couldn’t afford it.

New York in the 1850’s was split between opulence and poverty.  There were,

… men such as John Jacob Astor, a poor German immigrant boy who amassed $20 million trading furs and buying and selling New York real estate. Or George Law, who left his father’s upstate farm, walked to Troy, studied masonry, found work on the Delaware Hudson Canal and went on to make millions in construction. And then there was Cornelius Vanderbilt, the richest of them all, who launched a ferry service between Staten Island and Manhattan when he was only 16 and transformed it into a steamship and rail-empire. When the “Commodore†died in 1877, he was worth a staggering $100 million, about $2.3 billion in 2017 dollars.

The other side of New York was characterized by streets filled with the “detritus of modern life.â€

On those streets, ragged women carried bundles of broken boards and old timbers from demolished buildings, trailed by children loaded down with only slightly lighter burdens, Hobbled old men and shoeless scrawny girls in filthy cotton frocks carried cedar pails filled with ears of corn, trying to tempt well-dressed New Yorkers … Many of the vagrant children who wandered lower Manhattan — an estimated three thousand of them in 1850 — survived by scavenging or selling fruits, nuts, or petty merchandise.  Others stole from stores or the docks, or became pickpockets or junior members of adult gangs. In 1851, a fourth of the 16,000 criminals sent to City Prison were younger than 21 — eight hundred were younger than 15 and 175 were younger than 10. …

Arthur was ambitious and smart, and sought to be part of the opulent group in New York, but did not entirely abandon the principles his father had tried to instill in him.  In 1854, a young black woman named Elizabeth Jennings taught at the private Africa Free School, and, in a circumstance that foreshadowed that of Rosa Parks almost exactly a century later, was forcibly removed from a streetcar because the car did not have a placard that said “Colored Persons Allowed†displayed in its rear window.  Thomas Jennings, the girl’s father, sued the Third Avenue Railroad Company, and “hired the firm of Culver, Parker and Arthur to represent his daughter.â€

Chester A. Arthur was a junior partner in the firm and assigned the case.  He  won, and the jury awarded $225 to Jennings, and the court added another $25 for court costs. The Jennings decision began the process of desegregating all of New York’s streetcar lines (owned by different companies.)  The anniversary of the victory was celebrated by the Colored People’s Legal Rights Association for years after the event. Nothing appears in Arthur’s correspondence to suggest that he ever boasted of his triumph. But, related or not, it marked a turning point in his fortunes.

Shortly after the Jennings case, senior partner Culver was elected city judge of Brooklyn.  As a consequence, Arthur took on more and more of his work in the firm. In his letters to his sister, he worried about not having time for any sort of social life, and feared he would “become an old bachelor.’

Shortly after the Jennings case, senior partner Culver was elected city judge of Brooklyn.  As a consequence, Arthur took on more and more of his work in the firm. In his letters to his sister, he worried about not having time for any sort of social life, and feared he would “become an old bachelor.’

This was not to be the case. In 1856, he met his future wife, Nell Herndon, the cousin of a roommate. The story of Nell’s father, for whom Herndon Virginia (and other places are named), is a fascinating side trail in the book.

William Lewis Herndon was captain of the ill-fated steamship Central America. In 1857, he was already well-known for his exploration of the Valley of the Amazon.  He had a flair for writing and his naval reports were “so vivid Congress published 100,000 copies as a book.†On Wednesday September 9, 1857 the ship sailed into a rough storm while en route from Colon to New York City. Over the next few days, the Captain did his best to exude confidence, while at the same time taking all possible precautions. The ship sank the following Saturday and with it the Captain and more than 420 others (of 477 passengers and 101 crew).  The survivor accounts of the Captain’s conduct made him a national hero. Â

Arthur was in Kansas chasing another opportunity when the ship went down.

Nell sent Chester a telegram informing him of the disaster, and asking him to return to New York to help her and her mother settle the great man’s affairs. He immediately agreed to do so, cutting his Kansas adventure short. What’s more, the amount of gold lost on the Central America was so substantial it helped precipitate a financial panic and an economic slump, darkening the prospects of making a fortune in Kansas — or anywhere else.

The sinking of the Central America off Cape Hatteras on September 12, 1857, changed the course of Chester Arthur’s life. He left Kansas and returned to New York …

Back in New York he married Nell and looked for an avenue to support his new family in the manner they (especially Nell) craved.

Enter Thurlow Weed. Weed worked both sides of the aisle, despite being the undisputed boss of the Whig and later the Republican party. He was an interesting guy.

Enter Thurlow Weed. Weed worked both sides of the aisle, despite being the undisputed boss of the Whig and later the Republican party. He was an interesting guy.

Weed had a patriotic bent, and honestly felt that industrialization was the future of the country and genuinely thought his methods were necessary, justified and important. In this way, he differed from the machine bosses of which he was otherwise prototypical.

Known as “the Dictator,†Weed did not see his methods as antithetical to the democratic process and rationalized in a manner in which progressive politicians still do .. e.g.  “We know what’s good for you.â€

“Obnoxious as the admission is to a just sense of right and to a better condition of political ethics, we stand so far ‘impeached,’†Weed confessed in the Evening Journal when we was accused of pushing railroad-backed bills in exchange for donations to the party. “We would have preferred not to disclose to public view the financial history of political life … Public men know much of the “the rest of mankind’ are ignorant. We suppose it is generally understood that party organizations cost money and that presidential election especially are expensive.â€

Weed is an interesting character and had enough self-awareness to express his concerns on occasion about the choices he was making.

… [Weed] lamented that sometimes he mistook political allegiance for actual friendship.  “There is no course left but school myself into the belief that I have never understood the motives that governed me; and henceforth ‘to see myself as others see me.’  And yet it would have been more agreeable, in one’s old age, to feel that life had not been wholly wasted.â€

This is a comment that Arthur, in later years would probably have appreciated.

As Arthur’s involvement in Republican politics grew in the years preceding the Civil War, it undoubtedly led to some family strife. His wife came of a southern slave-holding family and was staunchly, if quietly, pro-secession.

When the war broke out, Arthur was appointed by New York’s governor, first as the representative to the Quartermaster, and then to Quartermaster.  By Greenberger’s account, Chester Arthur was scrupulously honest and efficient in the roles.

After losing the post due to a change in NY administration in 1863, Arthur decided to leverage what he had learned and make his fortune. While Nell might have been a southerner at heart, she appreciated the step up the financial ladder that was to come.

Arthur embraced the opportunity to bilk the government and justified it to himself because of his dissatisfaction with the Lincoln administration. It was at this time he made friends with the corrupt businessman Thomas Murphy, working as his lawyer, defending him from charges of selling defective clothing to the government for exorbitant prices. After the war, Arthur helped Murphy win a seat in the NY Senate. Arthur’s interests and character began to change.

Silas Burt, a fellow Union College graduate with a reformist bent, observed that Arthur “expressed less interest in the principles when agitating parties than in the machinery and maneuvers of the managers.â€

His standing rose steadily over the next few years in no small part thanks to his relationship with party boss Roscoe Conkling.

Conkling was probably not a nice man, but he was, pardon the phrase, a tough s.o.b. As a kid, he broke his jaw when a horse kicked him.

Conkling was probably not a nice man, but he was, pardon the phrase, a tough s.o.b. As a kid, he broke his jaw when a horse kicked him.

… but the incident didn’t diminish his love of horses or his good looks. On the afternoon of the incident, he sneaked out his bedroom to make and fly a kite. He loved to box, and was “very athletic, vigorous in his movements and easily superior to all others in the games and sports of childhood,†according to a classmate. He was “as large and massive in his mind as he was in his frame, and accomplished in his studies precisely what he did in his social life — a mastery and a command which his companions yielded to him as his due.

Greenberger’s portrayal of Conkling’s character and personality alone make it worth reading the book.

Conkling was the same age as Arthur and in the same profession.  As an attorney “he liked to bully witnesses and to make jurors weep.†He was self-assured and demanded respect as his due. In 1858 he was elected to Congress.

As sharp as Conkling was, he was not alone in his ability to be cuttingly sarcastic. He had a rival for oratory in the House – the representative from Maine – James Gillespie Blaine.

In April 1866, during a  debate over an Army reorganization bill,

Blaine accused Conkling of improperly receiving extra government pay for his work as a prosecutor in the court martial of an Army major. After a lengthy defense of his actions, Conkling concluded caustically that “if the member from Maine had the least idea how profoundly indifferent I am to his opinion on the subject he has been discussing, or upon any other subject personal to me, I think he would hardly take the trouble to rise here and express his opinion.â€

Blaine responded with a diatribe that cemented the eternal enmity between the two men — and which reverberated for decades to come. “As to the gentleman’s cruel sarcasm, I hope he will not be too severe,†Blaine sneered  “The contempt of that large-minded gentleman is so wilting, his haughty disdain, his grandiloquent swell, his majestic, super-eminent, overpowering, turkey-gobbler strut has been so crushing to myself and to all the men of the House, that I know it was an act of the greatest temerity for me to venture upon controversy with him.â€

The comment hit the mark, and Conkling never spoke to Blaine again.

In 1867, Conkling was elected to the Senate and stood out for his rapid rise in eminence in that body.  Newspapers began to take note of him, and this introduces another anecdote about Conkling’s temperament,

… the ladies’s gallery was always packed when Conkling was scheduled to speak. While her husband was in Washington, Julia Conkling preferred to stay in Utica, devoting herself to gardening and charity work. Julia’s absence fueled widespread rumors of Roscoe’s relationships with other women. According to one story, the editor of a weekly paper in Washington was poised to publish a long article about Conkling’s romantic exploits. The senator heard about it, confronted the editor, and demanded to see the proofs. After he read them, Conkling turned to the editor and calmly asked, “Do you intend to print this article?â€

“I do,†the editor replied.

“Then I will kill you,†Conkling said.

The editor’s assistant “saw the fear of imminent death seizing the soul of my chief.  There was in Mr. Conkling’s voice something so unspeakably fierce and cruel and his savage gaze something so appalling that few men, I think, could have withstood him.†The editor ordered the proofs destroyed and the story never appeared in print.

Conkling was to become one of Arthur’s closest friends.

More and more Arthur reflected the cynical character of his new associate.  When one of his friends remarked upon the change, Arthur issued a biting response,  “You are one of those goody-goody fellows who set up a high standard of morality that other people cannot reach.â€

Neither Arthur nor Conkling thought much of the “reformers†who criticized their political machine. Conkling rationalized it this way,

“It seems in some quarters, to be regarded as rather disreputable to belong to the Republican Party and to have battled for its maintenance,†Conkling huffed. “We are told the Republican Party is a machine.  Yes. A government is a machine; a church is a machine, an army is a machine; the common-school system of the state of New York is a machine; a political party is a machine.â€

“Every organization which binds men together for common purposes is a machine,†he continued. If its purposes are not honest, it should be hewn down and cast into the fire. But if its purposes are loyal and patriotic; if its aims are justice, civilization, progress, then it is a useful machine, and it ought to be preserved for the good that is in it.â€

Conkling was eventually to overplay his hand, starting with President Hayes and then Garfield, resigning his position in the Senate (thinking that his clout was such that the NY legislature would reinstate him.) Ironically, as Conkling’s political fortunes began to wane, those of his protege went in another direction.

Sadly, events in Arthur’s personal life did not correspond accordingly.  Personal tragedy struck when Nell died at 42 from pneumonia. Arthur was devastated.

Shortly after the death of his wife, against Conkling’s “advice†(demands), Arthur accepted the nomination to the vice presidency as a sop to the New York machine in exchange for support of Garfield’s nomination. It is here that Arthur begins the process of becoming his own man, once again.  He maintained his friendship with Conkling, but no longer would he comply with his dictums. He wanted to be Vice President.

Greenberger spares his readers from some of the heart-breaking account of Garfield’s drawn out death from an assassin’s bullet, but conveys the enormous impact it had on Arthur.(WWTFT highly recommends Destiny of the Republic, reviewed here.) It seems likely that the recent death of Nell in conjunction with the stress of his situation, made Arthur reassess some of his choices. But there was another, more unlikely contributor to Arthur’s change.Â

That person was Julia Sand, an invalid young woman who wrote him a series of letters, the first of which arrived when it looked like Garfield would succumb to his wounds and Arthur would become president.  In her first letter, Sand encourages Arthur and sympathizes with his position and expresses confidence in him, at a time when he is under incredible stress.  The letter arrived when he most needed it — when all were skeptical of him.  Some would blame him, as a member of the “stalwart†wing of the party, for Garfield’s death.  Others were dissatisfied by his unwillingness to seize control. He was heartsick at Garfield’s death and terrified of the unexpected responsibility.

It is difficult to extrapolate how much impact Julia Sand had upon Arthur since he never wrote back to her, although he did visit her briefly once. However, her letters do seem to correlate with Arthur’s actions, and they were preserved, unlike much of the documentation surrounding his life. Nevertheless, this reviewer is somewhat skeptical as to the degree attributed by the author of their significance to Arthur. They are very interesting to read, nonetheless.

Arthur went on to be the president that the country needed, did his best to fulfill the policies of his slain predecessor, and even repented from the corrupt machine from whence he had arisen. At the end of his life, he ordered all of the documents and letters from his time in New York, destroyed.

Arthur’s story is that of an imperfect man who accomplished a difficult task, that of reshaping his character.  “It is the tale of a man who veered off the right path, but rediscovered his better self…† This is a good book.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment