Saving Monticello by Marc Leepson

Marc Leepson’s extraordinary talent as a storyteller is matched by his prowess as a researcher.  His US flag book, also enjoyed by this reviewer, corrected the historical record and added to it. In this book, Leepson does that and more.

Marc Leepson’s extraordinary talent as a storyteller is matched by his prowess as a researcher.  His US flag book, also enjoyed by this reviewer, corrected the historical record and added to it. In this book, Leepson does that and more.

Thomas Jefferson has been called an American Renaissance man, and for good reason. His interests were wide ranging, as were his talents. The man who wrote the Declaration of Independence was also a bon vivant whose spending overtook his ability to pay. He spent lavishly to furnish Monticello and was seriously in debt before becoming the third US President. At the end of his presidency, he still owed his pre-Revolutionary War creditors a considerable sum. Unfortunately, plans to pay off that debt were frustrated by drought, crop failures and poor management of Jefferson’s properties. Instead of retiring his debts, he added to them. As was de rigueur for men of his social class, he continued to extend generous hospitality to his adult children, grandchildren and assorted relatives as well as to visiting artists, writers, and statesmen.

After the War of 1812, Jefferson’s financial condition worsened and he was forced to borrow to meet his bills, Repairs to Monticello were put off for better times.

When Jefferson died on July 4, 1826, he left a mountain of debt for his daughter and grandson to pay ($107,273.63). By the end of 1826, mother and son reluctantly concluded they would have to sell off Jefferson’s lands and household goods. According to an item in the Niles’ Register, the sale brought $47,840.

In the scramble to raise cash in the years after Jefferson’s death, Monticello continued to decay. Uninvited visitors pillaged house and grounds for souvenirs and worsened the general state of dilapidation. Upkeep was a continuing problem. Finally, in 1828 Martha and her son determined that Monticello and surrounding property would have to be sold. But land prices were low and the sale was delayed.

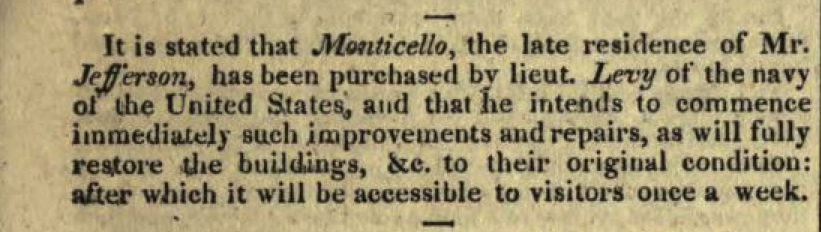

Finally in 1831, James Turner Barclay, a man of uncertain character and schemes, bought Monticello and 522 acres for $7,000. During the four and a half years of Barclay’s tenure the house deteriorated further. He also complained of increasing hordes of uninvited and destructive visitors. Barclay went bankrupt and sold Monticello and 218 surrounding acres to Uriah Levy for $2,700 in 1834.

In some quarters the purchase was met by an outpouring of anti-Semitism. Levy was accused of having acquired the property unethically. He was characterized as an uneducated “alien†whose ownership of the historic property was “a national humiliation.â€

Nothing could have been further off the mark. Uriah Levy was a fifth generation American, and the descendant of an accomplished family very much bound by patriotism to American history. Saving Monticello is as much about the Levy family as it is a history of Monticello. Leepson begins the Levy family story with Uriah’s great, great grandparent’s escape from the Spanish Inquisition

Uriah Phillips Levy was a naval hero of the war of 1812. He was the first Jewish U.S. Navy Commodore and is remembered for having fought to abolish flogging in the Navy and for overcoming anti-Semitism to attain the Navy’s highest rank.  During his long, checkered Navy career, Uriah’s impulsive and tempestuous nature caused him to be courts-martialed six times, but without substantively affecting his career.

Uriah Phillips Levy was a naval hero of the war of 1812. He was the first Jewish U.S. Navy Commodore and is remembered for having fought to abolish flogging in the Navy and for overcoming anti-Semitism to attain the Navy’s highest rank.  During his long, checkered Navy career, Uriah’s impulsive and tempestuous nature caused him to be courts-martialed six times, but without substantively affecting his career.

The US Navy considered him a hero. A WW II destroyer was named after him.  (The surrender ceremonies of the Japanese Navy were aboard this ship.) The first permanent Jewish Chapel built by the US Armed Forces is the Commodore Levy Chapel in Norfolk, Virginia, plus other honors. Leepson provides an intriguing account of Uriah’s naval career, including the story of the six court-martials. Extensive New York real estate holdings had also made Uriah a rich man.

Why did Uriah buy Monticello? No written record answers the question, but if evidence of his deep personal admiration for Jefferson is required, it should suffice that he commissioned a statue of Jefferson by a noted French sculptor1 and presented it to the nation.

During the 28 years of Uriah’s stewardship he spent a great deal of money restoring and maintaining Monticello. He also opened the home to visitors who wanted to pay homage to Jefferson’s memory.

When the Civil War erupted, Levy, then 61 years old, asked to be included in the Union effort. He was repeatedly put off until November of 1861 when he was ordered to take charge of the Navy’s Court-Martial Board in Washington!

He died in 1862 leaving a complicated will that bequeathed Monticello to the nation.

Monticello was seized by the South during the Civil War and again suffered neglect. Put up for sale by the Confederacy in 1864, it was purchased for $80, 500 by Lt. Colonel Benjamin Franklin Ficklin of the Confederate Army. Ficklin, another colorful character whose story Leepson weaves into the book, is the man who conceived the idea for the Pony Express and was instrumental in its organization.

When the war ended, Monticello reverted to Uriah Levy’s heirs who were still engaged in a lawsuit to overturn his will. The lengthy and complex legal machinations that resulted in the 1879 acquisition of Monticello by Uriah Levy’s Nephew, Jefferson Monroe Levy for $10,050, cannot be conveyed here, but during the years that the lawyers wrangled the property once again fell into disrepair.

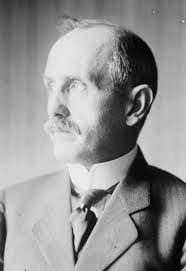

Jefferson Monroe Levy was as colorful a character as his Uncle Uriah He was a three-term congressman whom Leepson describes as a stock speculator, New York Lawyer, and real estate wheeler-dealer.

When he acquired Monticello the place was literally falling apart. He spent a fortune repairing and restoring the house and grounds. He filled the house with fine things, much as Jefferson had done. He attempted to locate original items that had been auctioned off so many years before. Mostly he furnished Monticello to suit his own expensive tastes, but preserved the architecture of the house as Jefferson had conceived it. He, too, entertained countless dignitaries at Monticello and opened the grounds to visitors.

When he acquired Monticello the place was literally falling apart. He spent a fortune repairing and restoring the house and grounds. He filled the house with fine things, much as Jefferson had done. He attempted to locate original items that had been auctioned off so many years before. Mostly he furnished Monticello to suit his own expensive tastes, but preserved the architecture of the house as Jefferson had conceived it. He, too, entertained countless dignitaries at Monticello and opened the grounds to visitors.

However, as the saying goes, no good deed should go unpunished. In 1911 Jefferson Levy had to fend off efforts to take the property from him. It was a nasty fight carried out in the newspapers and in Congress and exuded more than a whiff of the anti-Semitism his uncle had previously experienced.

Leepson writes, “The Levy family owned Monticello for eighty-nine years—far longer than the Jefferson family owned it.†Jefferson Levy vowed never to sell, but that was before he incurred huge losses in the stock market and in real estate. In a Jeffersonian redux, Levy was forced to sell his holdings to pay his creditors. He could no longer afford the upkeep of Monticello.

Congress would not pay his asking price and there were no other takers until 1923 when arrangements were made to sell Monticello to the newly formed, private, non-profit Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation. In the Foundation’s zeal to restore Monticello to Jeffersonian purity, all furnishings were removed and all traces of Levy stewardship were expunged. It took two centuries before the family who dedicated several fortunes to preserving Jefferson’s historic home was officially recognized and publicly honored. Thanks to Marc Leepson’s extensive research and raconteur’s skill, the past has been restored in a history that reads like a novel.

1Pierre Jean David d’Angers

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment