Perilous Fight by Stephen Budiansky

Stephen Budiansky’s Perilous Fight is a detailed exposition of just what the subtitle proclaims: America’s Intrepid War With Britain on the High Seas, 1812-1815. Intrepid, while a bold and colorful adjective, is exactly the right word. In using it, Budiansky is not only describing the early 19th century American fledgling navy, but also the scores of privateers under letters of marque that set out to plunder the British merchant marine. To understand what kind of men these were, you don’t have to go too far into Budiansky’s book.

Stephen Budiansky’s Perilous Fight is a detailed exposition of just what the subtitle proclaims: America’s Intrepid War With Britain on the High Seas, 1812-1815. Intrepid, while a bold and colorful adjective, is exactly the right word. In using it, Budiansky is not only describing the early 19th century American fledgling navy, but also the scores of privateers under letters of marque that set out to plunder the British merchant marine. To understand what kind of men these were, you don’t have to go too far into Budiansky’s book.

Not unexpectedly, the author begins his story with the legendary Commodore Preble and his adventures on the Barbary Coast. Preble had much to do with the forming of many of the key American captains of the War of 1812.

The following anecdote illustrating Preble’s famous disposition is reminiscent of an anecdote told of John Barry1 at the beginning of Tim McGrath’s excellent biography of Barry (reviewed here). They were of much the same character when at sea facing a potential enemy. Preble evidently wasn’t known for his patience.

One early and spirited display of his legendary short fuse, however, did him some good with the officers and men under his command, who were already growing weary of what one midshipman, Charles Morris, termed their captain’s “ebullitions of temper.† Nearing the Straits of Gibraltar on the evening of September 10, the Constitution’s lookout had spotted through the lowering haze just at sunset, a distant sail tracking the same course but far ahead. A few hours later, dark night settled in and they were suddenly on her: the same ship, apparently, and almost certainly a ship of war. The Constitution’s crew was brought swiftly and silently to their action quarters–no beating of the drums, but every gun crew at its station, gun ports open and guns run out, the men peering down their barrels at the stranger, slow matches smoldering at the ready to set off their charges the instant the order to fire came. Only then did Preble give the customary hail.

“What ship is that?â€Â

Across the water and defiant echo came back: “what ship is that?â€

“This is the United States ship Constitution. What ship is that?â€

Again the question was repeated, again with the same result. At which Preble grabbed the speaking trumpet and, his voice strained with rage, shouted, “I am now going to hail you one last time. If a proper answer is not returned. I will fire a shot into you.â€Â

“If you fire a shot, I will fire a broadside.â€

“What ship is that?†Preble thundered one last time.

“This is his Britannic Majesty’s ship Donegal, eighty-four guns, Sir Richard Strahan, an English commodore. Send your boat on board.â€

Now the volcano erupted. Leaping to the netting, Preble bellowed, “this is the United States ship Constitution, forty–four guns, Edward Preble, an American Commodore, who will be damned before he sends his boat on board any vessel.†And then, turning to his crew, he bellowed an equally loud, and theatrical, aside. “Blow on your matches, boys!â€Â

An ominous silence ensued, broken by the sound of a boat splashing down and rowing across. A shamefaced British Lieutenant. came on and apologetically explained that his ship was in fact the frigate Maidstone, no eighty-four-gun ship of the line at all. Her lookouts had been caught napping, and they had not seen the Constitution until they heard her hail; they had no expectation of encountering an American ship of war in these waters, and uncertain of her true identity and desperate to buy time to get their own men to quarters, they had stalled and dissembled.

The apologies were accepted; more important, as Morris later recalled, “this was the first occasion that had offered to show us what we might expect from our commander, and the spirit and decision which he displayed were hailed with pleasure by all, and at once mitigated the unfriendly feelings†that their commander’s irascibility had produced.

Perilous Fight is filled not only with anecdotes like this, but also a wealth of background information about the leadership of the navies on both sides of the Atlantic. Â The author does such a good job with his depictions of these people, that the reader finds himself in sympathy and admiration for some of the players on both sides of the fight.

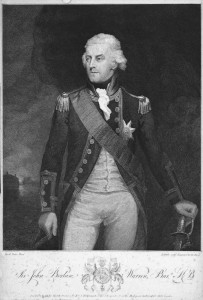

Anyone who has dealt with company politics or bureaucracies can’t help but sympathize with the man in charge of accomplishing a nearly impossible task, that of enforcing a blockade of all American ports, John Borlase Warren.

Warren was charged with bottling up thousands of miles of bays and inlets and preventing not only the wily American captains from using their “heavy frigates†to capture British prizes, but also faced with combatting hundreds of privateers under letters of marque.2 To top it off, Warren was under constant pressure from his boss across the Atlantic, John Wilson Croker (pronounced Crocker).

Warren was charged with bottling up thousands of miles of bays and inlets and preventing not only the wily American captains from using their “heavy frigates†to capture British prizes, but also faced with combatting hundreds of privateers under letters of marque.2 To top it off, Warren was under constant pressure from his boss across the Atlantic, John Wilson Croker (pronounced Crocker).

The author cites liberally from the correspondence between these two men, and one almost feels sorry for Warren at points. Budiansky refers to Croker as a man “who raised the withering of opponents and subordinates to an art form.â€Â It wasn’t that Croker was not competent or highly intelligent, but the fact was that he did not suffer fools, and didn’t want to hear excuses, however, reasonable. Warren, was by no means inept, but his task was nearly impossible. Nevertheless, he did pretty well during the War of 1812. As the flag admiral on the North American station, Warren was entitled to a 1/12 share of every American prize that was captured by British Men of War under his command.  Notwithstanding, the constant maintenance of large numbers of these, which kept them out of commission for long periods of time, it was still a lot of ships and meant a lot of money.

He was said to employ one clerk full-time just keeping track of his prize money accounts, and by the end of his first year of managing Great Britain’s war with America on the high seas the admiral’s take, even after deducting all those living expenses his agent had advanced, was 15,238 pounds, 16 shillings, and 2 pence — about $60,000 in 1812, the equivalent of something like $1 million today. He would receive another £13,602 in prize money a year and a half after that.

Croker eventually sent another man to act as his deputy and light a fire under Warren. Ultimately the admiralty relieved Warren of command, in favor of Admiral Alexander Cochrane, uncle of  the famous future Admiral Thomas Cochrane (the model for Patrick O’Brian’s Jack Aubrey).  Warren’s replacement would land a force under General Ross that would burn Washington D.C. and direct the bombardment of Fort McHenry.

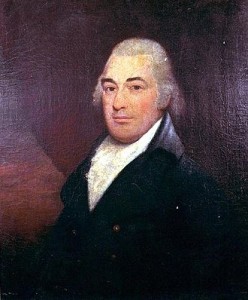

On the American side, Secretary of the Navy William Jones faced his own set of problems, and comes out pretty well in Budiansky’s account.

On the American side, Secretary of the Navy William Jones faced his own set of problems, and comes out pretty well in Budiansky’s account.

A man ahead of his time: Croker’s American counterpart, Secretary of the Navy William Jones, keenly grasped the importance of keeping a much more powerful enemy constantly off balance.

Jones’s strategy was to tie up an inordinate number of British resources finding and destroying a comparatively tiny opponent, blockading a huge coastline, and convoying merchant ships. Even toward the end of the war, when the British had succeeded in blockading most of the remaining American frigates; privateers and what remained of the American navy placed an unsupportable burden on the British.

The stunning effectiveness of William Jones’s countervailing strategy of striking at British commerce with small and fleet vessels was not lost on observers, either. With two sloops of war, an improvised supply system, and empty coffers, the American navy by the end of the summer of 1814 had succeeded in making the cost of the war intolerable to the British merchant classes that had once been the most ardent advocates of vigorous prosecution of the war against America. Had the United States entered the war with the ships and money and efficient organization to fully realize Jones’s commerce-raiding strategy from the start, the war might have been over in the summer of 1813, and on terms American might have had even more power to choose.

Jones not only pursued a sound strategy throughout the conflict, but was also responsible for reforming and organizing a department that was in shambles when he took over. Additionally, he was burdened with serving as the acting Secretary of the Treasury while Gallatin was pursuing diplomatic avenues in Europe, during much of 1813-14. To say he was overworked would be an understatement. It was a thankless task and nearly ruined him financially.

On top of all this, he was faced with controlling a number of very strong characters and getting them to adhere to his strategy. Some of the very characteristics that made the American naval captains so successful at the beginning of the conflict, were sometimes at odds with the overall strategy that Jones sought to implement.

The political capital derived from the navy’s early victories seemed to be at odds with this strategy. Captains on both sides of the conflict tended to view their ships as their personal ticket to glory and fame. This was exacerbated by the British shock at losing several ships in succession, and competitive fury amongst the American captains stoked by these early victories. When Hull took HMS Guerrier with the USS Constitution, the people were ebullient, as is evidenced by this little ditty sung to the tune of Yankee Doodle.

Come, come my lads, the glasses raise;

Let’s drink to the gallant Hull, Sir,

For well, our Constitution, he

Sustain’d against John Bull, Sir.

Where’s now the Guerrere? Deep she sinks

Beneath old Neptune’s Acres;

Hull, Hull’s the lad, will make them glad

To bear away with Dacres.

Our good Live Oak ‘gainst British Oak

On Ocean shall maintain, Sir.

With Yankee balls and Hearts of Oak

Its claims to Ocean, vain, Sir.

Both the British admiralty and the American Secretary of the Navy issued explicit orders to avoid single ship contests. Jones realized that America could little afford to lose any of its few ships, and the British leadership saw it as a needless risk, given the overwhelming odds in their favor. Nor did they want to suffer any more public outcry at any more losses. Orders notwithstanding, Captain Lawrence risked and lost the USS Chesapeake to Captain Philip Broke of HMS Shannon.

It was a fierce and bloody engagement in which Lawrence was killed and Broke was horribly wounded.

Broke arrived at the Chesapeake’s forecastle just as Lieutenant Budd appeared from below and tried to rally his remaining men; a furious musket blow from an American sailor left Broke momentarily stunned, and a second American brought a cutlass down with full force, shearing off Broke’s scalp and cutting through the skull to bare his brains; a British sailor then ran Broke’s assailant through, and by that point the battle was essentially over, even if the blood-maddened fury continued for several minutes. …

Incredibly, Broke survived, and was accorded much honor and acclaim. But his life at sea was over. In the wake of this single-ship action, both sides’ leadership quietly and firmly reiterated their orders in no uncertain terms.

Not all of the engagements between the British and the Americans ended so bloodily. However successful against merchant shipping, American privateers were rarely a match for the British navy.

Ill-disciplined crews and incompetent commanders on a number of occasions led to privateers’ blundering directly into enemy hands. …. American privateers sometimes threw away their considerable sailing advantages through misjudgment and atrocious seamanship …

Budiansky provides several humorous examples such as this one:

Another American privateer captain, mistaking a British seventy-four3 for an Indiaman4, ran his ship alongside and hailed the British ship to strike her colors. “I am not in the habit of striking my colors,†the British captain called back, and at the same moment all three tiers of gunports flew open. “Well,†the American captain replied, “if you won’t, I will.†Â

There is a great deal more to say about Budiansky’s book, but unfortunately it is beyond the scope of this review to cover it all. However, this reviewer would be remiss not to mention a few particulars about the quality of the research and writing.

Budiansky makes historical characters into real people by liberally quoting from contemporary sources and first-hand accounts. Not only is the research superb and the author’s conclusions sound, they are well-explained. The author included numerous maps and diagrams, making this book one of the most accessible and understandable naval histories this reviewer has had the pleasure of reading. His diagrams of naval engagements were hugely beneficial for helping the reader understand what happened, when.

The author also included a number of photographic inserts of paintings of the major characters and surviving documents.  giving the reader a face to place with the caricatures so aptly drawn by Budiansky’s words.

The bibliography is spectacular and will delight any reader who wants to delve further. Archive.org has many of the now-out-of-print books cited by the author.

Perilous Fight is well worth reading for anyone interested in the War of 1812 or American naval history.

- Interestingly, although considered by some as the father of the American navy for his exploits in the American Revolution and for his “floating naval academy,†Barry merits only a brief mention on one page in Perilous Fight, with no details about his impact on the careers of those who fought during the War of 1812.

- In an aside, Budiansky provides a good explanation of the difference between a privateer and a letter of marque. “Although the term “privateer†was often used to refer to any private armed vessel, distinction was usually drawn between privateers in the strict sense, whose only purpose was raiding enemy shipping, and letters of marque, whose major purpose was to carry a cargo, employing their arms to fight their way through or capture any prizes they fortuitously happened upon the way.â€

- Seventy-four: A seventy-four gun ship of the line. One of the largest classes of British warship during the war.

- Indiaman: East Indiamen were the largest merchant ships regularly built during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, generally measuring between 1100 and 1400 tons burthen. Wikipedia

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment