Lincoln’s Gamble By Todd Brewster

Lincoln’s Gamble

Lincoln’s Gamble

By

Todd Brewster

The Lincoln in Todd Brewster’s book seems the alter ego of the Lincoln in Richard Brookhiser’s Founder’s Son. While the two authors cover some of the same material, this reader came away from Lincoln’s Gamble with an equivocal impression of the 16th president. Indeed, Brewster states in his introduction that at least part of his purpose in writing the book was to pare away hagiographic portrayals of Lincoln —“still conveyed to school children todayâ€â€”to reveal a more conflicted and flawed man.

In fairness, Brookhiser’s book is more global and thus more balanced. In his Introduction he writes: It is the history of a career, and the unfolding of the ideas that animated it. Brookhiser’s Lincoln finds moral grounding in the principles laid out in the Declaration and reason in their articulation as law in the Constitution. But that not withstanding, his Lincoln is often beset by depression, indecision and doubt.

Brewster’s focus is on a single event, the Emancipation Proclamation, and the six months, from July 1862 to January 1863, that preceded it. It was a time of great angst for Lincoln as Commander and Chief as well as politically and personally. The war was going badly. Union generals failed to do battle with the vigor necessary to win decisively and stop the carnage. Public support for the war and for Lincoln was waning and the next presidential election was less than two years away. Lincoln was beset by “a cabinet of rivals,†many disloyal to Lincoln and openly critical of his conduct of the war. On a personal level, he was grieving over the February death of his eleven-year-old son Willie and, at the same time, coping with Mary Todd Lincoln’s sorrow and its manifestations of mental instability. Add to that Lincoln’s searing doubts about God’s purpose in allowing the terrible bloodletting to continue without resolution.

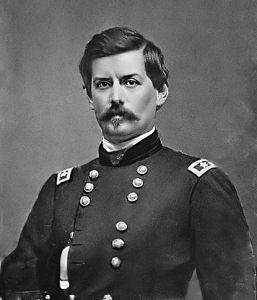

In April of 1862, General George B. McClellan’s bungled the opportunity to capture Richmond, “probably the last chance for the Union to make it a short war.†Historians often describe McClellan as risk averse, Brewster sees McClellan’s failures as reluctance to wage war on “his own people.â€

In April of 1862, General George B. McClellan’s bungled the opportunity to capture Richmond, “probably the last chance for the Union to make it a short war.†Historians often describe McClellan as risk averse, Brewster sees McClellan’s failures as reluctance to wage war on “his own people.â€

Like many of the West Point officers serving the Union, McClellan was a Democrat. He did not share the Republican Party’s antipathy toward the South, nor did he see the eradication of slavery as a worthy war goal…

McClellan was particularly uncomfortable with bringing a war against his own people. Throughout his life he has felt himself inclined toward Southern culture and Southern thinking, preferring it to Northern ways, even as he held firm to the belief that the South’s decision to secede was wrong.

Such a confusion of sympathies produced a stuttering performance. In McClellan’s view, radicals on both sides brought about the rebellion. He did not want to turn it into a full scale Civil War. By avoiding aggressive strategies he could limit Union and Southern bloodletting.

In early July, Lincoln visited McClellan at his Virginia headquarters. McClellan, whose outsized opinion of himself left no room for other considerations, decided Lincoln needed “a frank letter†laying out the “proper†conduct of the war. According to McClellan, that should be fighting:

A gentleman’s war ….the general asserted that victory should only be pursued “according to the highest principles known to Christian Civilization,â€which, to McClellan, included a prohibition on the “confiscation of property, [on] political executions of persons,†and on “forced abolition of slavery.â€

Lincoln read and pocketed the letter without comment, but he not only rejected McClellan’s counsel, he determined to free the slaves. The decision presented Lincoln with great difficulties. Although he found slavery morally repugnant, he had stated over and over again that the Constitution protected it in the states where it already existed just as it reflected the founder’s desire to prohibit its spread.

“Lincoln may have been a moralist but he was also, perhaps primarily a lawyer, resigned to working with the law as it was, not as he wished it to be. (Author’s emphasis.)

On more than one occasion he had publicly advocated a gradual and negotiated end to slavery that included compensation for former masters. But the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act, which repealed the 1820 Missouri Compromise, made slavery an urgent issue.

Yet, was there a gradual path to be found on an issue divided by such absolutes? Four years after his celebrated contest with Douglas, two years into the bloody national struggle he had so feared, caught up in this miserable 1862 summer of death, Lincoln, his confidence shaken by months of failure, set himself to sketch a document he hoped would wrest the nation from the grip on annihilation.

He needed to craft an order that would not only withstand judicial scrutiny, but one that Lincoln, defender of the Constitution, could justify. Slaves were legal property and the Constitution protected private property from government taking. An executive order of emancipation was beyond the powers of the president, “but not. Lincoln concluded, if such an order were issued as furtherance of the executive’s war powers.â€

Brewster points out the ironies of that decision. If it was an act of military necessity it could only apply to the slaves in the states that were in rebellion, since there was no military necessity to free slaves in states that were not in rebellion.

Among other difficult to justify aspects of the Emancipation Proclamation was Lincoln’s often-repeated statement that the war, first and foremost, was to save the Union, not to free the slaves. He had never been an abolitionist and had grave doubts about the practically of immediate emancipation. His concern, one shared even by some abolitionists, was that the two races could not live together in harmony and that emancipated slaves, unprepared to make their own way, would resort to crime and become a threat and a burden.

Even more troubling, Lincoln could not predict the consequences he and the nation might suffer as a result of his Proclamation. Would a change of mission result in a coup d’etatby McClellan and others who committed to fight for the Union but not to bring down slavery? Would abolitionists pillory him for leaving some slaves in servitude? Would it drive border states into the Confederacy?

Emancipation might also prove a failure even as a military tactic, either because the freed slaves would choose to stay with their masters and fight for the South, bolstering the Southern cause rather than eroding it, or because freeing the slaves would precipitate what so many, including Lincoln, had long dreaded: an all-out race war, a bloody expression of long-suppressed rage that would spread uncontrollably, engulfing the nation.

It was risk-taking writ large. It was Lincoln’s Gamble

Lincoln wrote and rewrote the Proclamation finally presenting it to his cabinet on July 2, 1862. After all had their say, Seward advised Lincoln to wait “until you can give it to the country supported by military success†lest it look an act of desperation, “the last measure of an exhausted government, a cry for help…â€

Lincoln was convinced by Seward’s argument and continued to tinker with the document over the coming weeks. He also pursued his plan for colonization: to send the freed slaves along with all free members of their race to a colony in Africa. Colonization had the support of many groups that agreed on little else. One group that did not support the idea was “a small but significant black elite†of free blacks who called the proposed policy “inexpedient, inauspicious and impolitic†and met with Lincoln to tell him so, but without effect.

Lincoln had to wait for Antietam to follow Seward’s advice. Fought on September 17, 1862, it was the single bloodiest battle in American history. McClellan again failed to press his numerical advantage and destroy Lee’s Army, allowing it to withdraw without interference. Hardly the hoped for decisive battle but it would do. On September 22, 1862 rd Lincoln proclaimed that, effective January 1, 1863…

Lincoln had to wait for Antietam to follow Seward’s advice. Fought on September 17, 1862, it was the single bloodiest battle in American history. McClellan again failed to press his numerical advantage and destroy Lee’s Army, allowing it to withdraw without interference. Hardly the hoped for decisive battle but it would do. On September 22, 1862 rd Lincoln proclaimed that, effective January 1, 1863…

“…all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom…

Lincoln was shaken by the terrible carnage and furious with McClellan for failing to pursue Lee, despite Lincoln’s order to do so. He relieved McClellan of his command and determined that, henceforth the war would be waged very differently.

Brewster and Brookhiser both expound on these perilous times but the authors’ presentation of these events often vary. It is not facts but emphasis that diverge as in their accounts of Lincoln’s December 1862 Annual Message to Congress (state of the union address).

Brookhiser writes:

The conclusion of his second Annual Message to Congress, given in December of 1862, showed him finding his range. His topic was how the end of he war might be hastened by ending slavery. Lincoln wanted to impress Congress with the magnitude of the question and the weight of their shared responsibility, and he finished with three rhetorical strokes, like chimes. “The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present.†This was an attempt at loftiness—a failed attempt. There was a little too much horsehair stuffing in it. After a few beats, Lincoln tried again: “We cannot escape history.†This was better, a statement as simple as it was sweeping. Then after a few more beats, bulls-eye: “We shall nobly save, or meanly lose, the last best, hope of earth.†This was as lofty as Henry Clay at his most eloquent; it was sweeping, surveying all of history.†This was better, a statement as simple as it was a sweeping, surveying of all of history; the cluster of monosyllables, varied by only two adverbs, seems as plain as dirt, but there is gold dust in it: the sliding ls, is the very intonations of loss, are stopped by the sharp almost-rhyme of last/best.

Words alone do not win wars or lead men, but what words could do, Lincoln’s would.

Brewster’s take on the same address is quite different.

For Lincoln there may be no more peculiar piece of writing, none in his gifted history as a man of words, than this strange, disjointed, sometimes contradictory address.

Brewster then devotes the next eight pages to that analysis. Summing up, he observes that the body of the speech clashed with the conclusion:

The words are inspiring –they are often quoted even today–but they likely confused their listeners in the moment. Several keys phrases had to have lingered in the ear for their awkward juxtaposition with his new plans. While Lincoln derided the “dogmas of the past†he had just proposed their slow and steady continuation. And if he wished the old ideas to be discarded for new, then why in this very speech had he returned to, and even expanded upon ,proposals—colonization; gradual, compensated emancipation—that he had made before and that had failed before?…

…Slavery was done, he was saying. History had already marked it for extinction. The only question was how it was to be made extinct, and here Lincoln was saying that the how could either be through more acts of war or it could be the “plain, peaceful, generous, just†proposals he had just put before the country, a way which, if followed, the world will forever applaud, and God must forever bless.â€

Readers can judge which is an accurate exposition of the speech and Lincoln’s motives and intentions. Did Brookhiser gloss over the first part of Lincoln’s address? Does Brewster unfairly belittle the conclusion that Brookhiser praises?

This reviewer has already recommended Brookhiser’s Founder’s Son and also commends Brewster’s Lincoln’s Gamble. His detailed account is an important addition to understanding the Proclamation and the circumstances of its genesis. The book is well researched and Brewster writes well, if somewhat acerbically.

These books remind that history is more than “what happened†and may be shaped by the historian’s predispositions. Whether such is the present case can only be determined by reading both books.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

2 comments

Interesting article. It makes me want to read both books about Lincoln.

[Reply]

Reading them, one after the other, is not only an opportunity to learn more about Lincoln and the Civil War period, but to compare two authors’ approach to similar material. I encourage the reading of both books.

[Reply]

Leave a Comment