A Disease in the Public Mind A New Understanding of Why We Fought the Civil War By Thomas Fleming

A Disease in the Public Mind

A Disease in the Public Mind

A New Understanding of Why We Fought the Civil War

By Thomas Fleming

The author’s claim that he offers a “new understanding†seems overblown to this reviewer. Truth to tell, there is little in this book about the American Civil War that hasn’t been covered by other historians. Fleming’s contribution is more a matter of emphasis than originality.

That having been said, this is an interesting and readable book. In the course of Fleming’s narrative he casts light on some little discussed related events, one of which will be addressed later in this review.

The author begins by citing facts known to those familiar with the period but may not be known to others. In any case they bear repeating because they underscore the horrific dimensions of the conflict.

Historians believe the combined Union and Confederate toll was at least 750,000 but it could be as high as 850,000 because of the difficulty of arriving at an accurate count of Confederate dead. “Confederacies records vanished with their defeat.â€

This much is certain: more soldiers died in the four year struggle than the nation lost in all her previous and future wars combined.

Fleming puts this in comparative terms.

What makes these numbers especially horrendous is the fact that America’s population in 1861 was about 31 million. In 2012, U.S. population is about 313 million. If a similar conflict demanded the same sacrifice from our young men and women today, the number of dead might total over 10 million.

The enormity of the tragedy is compounded by the fact that America is the only country in the world that fought a war to end slavery. Other nations with large slave populations ended slavery with relatively little bloodshed.

Especially perplexing is that a mere 316,632 southerners owned slaves – 6 percent of the total white population of 5.582,322 and only 46,214 of these owned 50 slaves or more. “Why, then, did the vast majority of the white population unite behind these slaveholders in a fratricidal this war†that would take the lives of over 300,000 of their sons “to preserve an institution in which they apparently had no personal stake?†The author’s answer is the title of his book.

He defines “A Disease of the Public Mind†as:

…fixed beliefs that are fundamental to the way people participate in the world of their time. A disease of the public mind would seem to be a twisted interpretation of political, or economic, or spiritual realities that seize control of thousands or even millions of minds.

Fleming argues that southern radicals and fanatic northern abolitionists so inflamed the public mind that the Civil War was the inevitable result. This thesis rests on the assumption that the war might have been avoided if not for these agitators and slavery might have eventually ended without a war. These seem dubious assumptions at best.

The invention of the cotton gin, as the author notes, increased the economic importance of slavery. The 1808 U. S. and British ban on importing or exporting slaves increased the monetary value of the slaves themselves. Equally important, southern political power depended on the Three-fifths Compromise made by the Continental Congress in 1783. The Compromise was an agreement to count three-fifths of a state’s slaves in apportioning Representatives, Presidential electors, and direct taxes. From 1800 to the 1850s, the three-fifths rule was instrumental in electing slave-holding presidents. But, as northern states grew more rapidly, southern political power increasingly depended upon the admission to the Union of new slave-holding states. Morality aside, northern political interests conversely resided in blocking their admission.

William J. Cooper in his book “We Have the War Upon Us†(reviewed here) lays out the political exigencies that caused the Civil War. He concludes that, contrary to what most Americans today believe, although the war ended slavery it was not fought for that reason. Cooper’s book is about the men whose decisions, action or inaction culminated in the Civil War.

Fleming makes his case by describing the “disease of the public mind†that extremists on both sides of the slavery issue perpetuated.

As the number of slaves equaled or exceeded the white population in southern states, white southerners became fearful of a slave rebellion. Radical abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison and others played on that fear, repeatedly warning that unless the slaves were immediately freed, the South would be plunged into a bloody race war. Garrison and others gave John Brown, a lying, murdering, self-aggrandizing madman, hero status in the North. In addition, Garrison vilified southerners. Labeling them cruel, decadent and lazy. Fabricated stories in abolitionist newspapers “proved†these accusations.

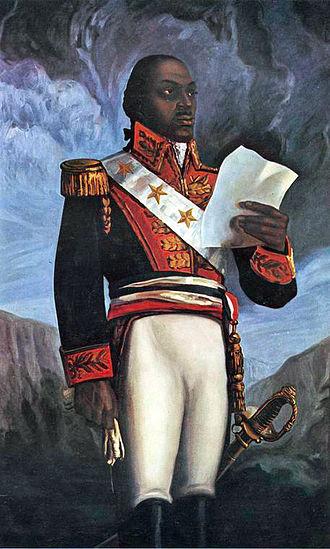

Events in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) lent credence to Garrison’s frightening prognostications of race war. When the Jacobins took control of the French National Assembly in 1797, they issued a declaration freeing all the slaves in France’s overseas dominions. When word reached Saint-Domingue, a slave uprising destroyed hundreds of sugar, coffee and indigo plantations. Black leader Toussant Louverture preached equality between blacks and whites, declared himself ruler for life, and began creating a multiracial society.

Events in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) lent credence to Garrison’s frightening prognostications of race war. When the Jacobins took control of the French National Assembly in 1797, they issued a declaration freeing all the slaves in France’s overseas dominions. When word reached Saint-Domingue, a slave uprising destroyed hundreds of sugar, coffee and indigo plantations. Black leader Toussant Louverture preached equality between blacks and whites, declared himself ruler for life, and began creating a multiracial society.

However, in 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte seized power in Paris and set about restoring the French colonial empire. He sent French diplomat Louis-André Pichon to President Jefferson to ask about Saint Domingue.

Jefferson’s reply exceeded Pichon’s most sanguine hopes. The new president urged Pichon to tell his government that America was eager to help restore French rule in Saint-Dominque. He welcomed France’s proposal to send an army to crush the black rebels. ‘Nothing will be easier than [for us] to furnish your army and fleet with everything to reduce Toussant to starvation,’ Jefferson said.

Unknown to Jefferson, the larger purpose of’ the expedition was to get Spain to retrocede the territory of Louisiana to the French. As soon as French supremacy was restored in Saint-Domingue, Bonaparte intended to send his army to New Orleans.

Louisiana would supply Saint-Domingue and the other French West Indian Islands with food at cut-rate prices, eliminating the need to buy from the Americans.â€

The upheaval in Saint-Domingue caused a number of white French planters to flee to America where they recounted their harrowing experiences. Rumors circulated in the southern states that American slaves, knowing of the events in Saint-Domingue, were plotting similar uprisings. A thwarted slave revolt in Virginia intensified Jefferson’s fear that unless the successful rebellion in Saint-Domingue was ended, it would inspire more slave uprisings in the South.

The French prevailed and imprisoned Toussant, but Bonaparte made a ruinous blunder. He decided to re-impose slavery on Saint-Domingue and other French islands. The blacks rose in fury, bested the French and undertook the extermination of the white population. They renamed the island Haiti.

Jefferson had helped to create a wrecked and desolate island in the grip of an illiterate, half mad despot. Haiti’s blood soaked birth made the ultimate meaning of the term race war an unforgettable nightmare. It was soon on its way to becoming “a disease of the public mind†in the southern states.

When the news of the slaughter reached Jefferson he determined that Haiti had to be “as isolated as possible from the United States of America.†A few months after the slaughter Jefferson’s son-in-law introduced a resolution in the House of Representatives calling upon the United States to refuse to recognize Haiti’s independence. “Everyone knew this was a message from the president. It passed overwhelmingly.â€

Why did President Jefferson manage to escape without a word of reproach or criticism, both in the North and the South, for the awful fate he had helped to impose on Haiti? Few people beside James Madison knew about the president’s approval of Napoleon’s invasion. The public blame fell on France.

Even if the whole truth were known, there is another reason why most Americans would probably have found little fault with the president: the Louisiana Purchase.

Bonaparte, in desperate need of money for his war machine, sold Louisiana to the United States. In July 1803, 868,000 square miles, a third of the continent was purchased by the United States for $15 million.

“The acquisition guaranteed Thomas Jefferson’s popularity for decades to come. In 1804 he was reelected by an overwhelming majority.â€

Thomas Jefferson’s noble sentiments in the Declaration of Independence and the existence of slavery were irreconcilable as many of the Founders realized, including Jefferson. For all of Jefferson’s reported agonizing over slavery he left himself a convenient out in his insistence that blacks were an inferior race and poorly suited for life among whites.

Alexander Hamilton disagreed. In a letter to John Jay, urging support of a plan to enroll blacks to fight in the Revolutionary War, Hamilton declared such claims were “founded neither in reason nor experience.” but on white reluctance to part with “property of so valuable a kind.â€

Despite the condemnation of some historians, there was a limit to how far the Founders were able to go and keep the South from forming a separate nation. A series of political compromises in subsequent years attempted to placate the southern states while preserving the Union. Ultimately, in the months immediately preceding the outbreak of hostilities, Congress ran out of compromises.

Fleming’s argument — that fanatics in the North and South drove the nation into an avoidable war — doesn’t add up nor does the notion that slavery would have eventually withered away. How long that withering might have taken and what its effects would have been on future generations of blacks and whites, and on the nation as a “beacon of freedom in the world†are issues Fleming does not explore.

The title phrase in Fleming’s book has a rich patrimony. In 1859 James Buchanan blamed John Brown’s recklessness on “an incurable disease in the public mind.†Lincoln also invoked the “public mind†when he accused the South of “debauching the public mind.†Adlai Stevenson, Democrat presidential candidate in 1952 and 1956, declared: “Those who corrupt the public mind are just as evil as those who steal from the public purse.â€

Stevenson’s condemnation has special meaning in our time. The disease that infects the public mind today is that economic equality is more important than freedom. In the present case, the evil includes stealing from the public purse.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

7 comments

Haven’t yet read the book, so I can’t comment specifically on its content. But in general, I have a problem with any moral equivalence between abolitionists and southern fanatics. Abolitionists were fanatics in the cause of human freedom, while the fire-eaters were fanatics in the defense of slavery. The abolitionists may not have been politically astute, but theirs was as noble a goal as it is possible to conceive.

[Reply]

Marcia Reply:

October 9th, 2013 at 10:30 am

I have no argument regarding the abolitionists’ moral position, but more than good intentions were required. Their intransigence regarding compensation for freed slaves, which totally ignored economic realities, made it difficult, if not impossible, to avoid war despite the best efforts of Seward and Lincoln to find a way out of the impasse. The radical abolitionists’ vituperative attitudes and unreasonable demands during reconstruction did neither the South nor the newly freed slaves any good. Only assorted Northern crooks and politicians benefited and they left a bitter legacy.

[Reply]

Brian Reply:

October 9th, 2013 at 12:08 pm

Marcia,

As I recall, the principal basis upon which abolitionists opposed gradual, compensated abolition before the Civil War was not the compensation but the timing. That is, they were opposed to schemes which, for example, emancipated all slaves born after some date, or 21 years after some date, etc.

The real opposition to such programs, however, came from slaveholders themselves, and their supporters. For instance, several politicians (including Lincoln, in his one term in Congress) supported gradual, compensated emancipation in the District of Columbia, where they believed Congress had the authority to emancipate. This plan was violently opposed by the Southerners. Even during the Civil War, Lincoln tried to get the Border States such as Kentucky to adopt a gradual, compensated plan of emancipation, and they refused. They refused, in spite of the fact that it should have been obvious to them that the days of slavery were numbered, as Lincoln tried to tell them.

You also claim that after the war “The radical abolitionists’ vituperative attitudes and unreasonable demands during reconstruction did neither the South nor the newly freed slaves any good.” I’m not sure what attitudes and demands you’re referring to. All that the one-time abolitionists, and decent people everywhere, demanded for the freedmen was that they have the same rights as everybody else, and even this proved way too much for the Southern “redeemers.” What should have happened was the implementation of some version of “40 acres and a mule.” That is, the big plantations belonging to senior Confederate politicians and officers should have been confiscated and distributed to the freedmen.

I also take issue with your statement that “Only assorted Northern crooks and politicians benefited and they left a bitter legacy.” In addition to sounding like something right out of Birth of a Nation, it ignores the very real advances in education and even the attainment of political office by Blacks in the immediate aftermath of the war. It was the combination of Andrew Johnson’s racist and incompetent version of Presidential Reconstruction, and ultimately the withdrawal of US troops after the sordid deal which gave the presidency to Hayes over Tilden which let unreconstructed, racist, ex-Confederates return to power and impose a century of post-war apartheid on the South.

[Reply]

Marcia Reply:

October 9th, 2013 at 3:10 pm

Charles Sumner, Thaddeus Stevens and other radicals opposed compensation for freed slaves under any conditions.

They wanted to exact retribution not only from the slave owners, but from all Southern whites (the vast majority of whom owned no slaves). Lincoln was at odds with the radicals in his own party over Reconstruction and Johnson inherited their animus. This is not to excuse the fire breathers of the South who had their own axes to grind.

We will have to agree to disagree about whether reconstruction was beneficial for the freedmen, many of whom were shamelessly used and manipulated by their “friends.” The fact that the South remained economically devastated when Reconstruction ended speaks for itself.

As to forty acres and a mule confiscated from “senior Confederate politicians and officers,” you must have a different version of the Constitution than I have. Please see the review of “A Massacre in Memphis” for more on this topic.

As William J. Cooper points out in his book, “We Have the War Upon Us,†it is very difficult to see the past through the imperfect eyes of those who lived it, and not with our own omniscient twenty-twenty vision. Please see that review also for his exposition of the political and social contexts of the years prior to the war.

Finally, thank you for taking the time to comment. WWTFT welcomes and encourages comments from engaged readers like yourself.

[“Fleming’s argument — that fanatics in the North and South drove the nation into an avoidable war — doesn’t add up nor does the notion that slavery would have eventually withered away.”]

Considering that slavery or forced labor still exists in this country and in other parts of the world, I cannot help but agree with you. I think Fleming may have been indulging in some kind of fantasy in which he believed that some kind of compromise could have been reached.

I find it odd that the historian literally seemed aggressive over the idea of the colonial elite waging war in order to break away from Britain. But in the case of freedom for slaves, he advocates compromise and gradual emancipation . . . as if it would ever happen.

[Reply]

[“Charles Sumner, Thaddeus Stevens and other radicals opposed compensation for freed slaves under any conditions.”]

Actually, it was President Andrew Johnson and his supporters. Please get your facts straight.

[Reply]

You are correct that Stevens and Sumner softened their opposition to compensating slaveholders if it would hasten emancipation.

In May of 1855 Sumner gave a speech in which he explained his justification for compensation:

“Shrinking instinctively from any recognition of rights founded on wrongs, I find myself shrinking also from any austere verdict which shall deny the means necessary from the great consummation we seek…I am disposed to consider the question of compensation as one of expediency, to be determined by the exigencies of the hour, and the constitutional power of the government; though such is my desire to see the foul fiend of slavery in flight, that I could not hesitate to build even a bridge of gold, to promote his escape.” Not exactly an enthusiastic endorsement of the idea but an accurate one at that stage of events.

[Reply]

Leave a Comment