Angry Mobs and Founding Fathers by Michael Newton

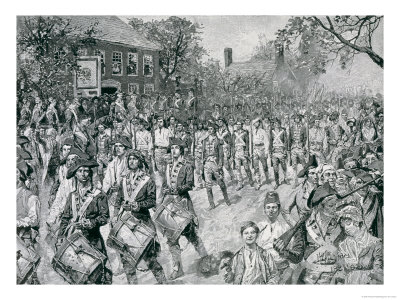

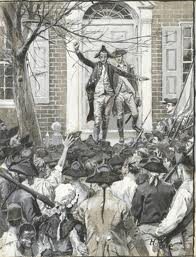

Michael Newton’s latest book, Angry Mobs and Founding Fathers, is a densely packed, meticulously researched, compendium of historical knowledge. Newton has done a great job assembling a formidable bibliography1of both original sources and the works of respected historians, synthesizing them into an exposition of the forces responsible for the American experiment. Newton documents the disparate roles played by “angry mobs” and by “Founding Fathers.” These two forces were not always in sync with one another. At times the irascible mobs were in control, and the aristocratic Founders struggled to reign them in, guide their passions, or even just keep up. At other times, like during the period of Constitutional Convention, it was the Founders who struggled to convince the masses of the efficacy of their plans. The Founders learned to harness the power of a willful, independent people, and use it to ensure the success of the American experiment. But, at times they struggled to keep up with the enthusiasms and power of populism. Newton cites many of the books reviewed here at WWTFT, as well as many others. He is able to sift the salient points remarkably effectively in such a deceptively short volume. Newton explores the motivations of the “angry mobs” and Founding Fathers, from the colonial period, through the American Revolution, the failure of the Articles of Confederation, the Constitutional Convention, and Ratification. Newton clearly depicts the ebb and flow of power and participation between these two groups. He points out how, during the first part of the struggle for independence, it was the angry mobs more than the Founding Fathers, which drove the Revolution. In some sense, the angry mobs forced the issue. This is a thesis supported by writers like Gordon S. Wood, Harlow Giles Unger, T. H. Breen, and others. However, Mr. Newton explicitly details the ebb and flow of political force.  The “angry mobs” forced the issue and dragged the country into war with their precipitous actions. Once the country was involved, whether they liked it or not, the aristocratic Founders managed the effort with men like Washington. However, it was a precarious balance between the two forces as Alexander Hamilton wrote of the army in 1780,

Michael Newton’s latest book, Angry Mobs and Founding Fathers, is a densely packed, meticulously researched, compendium of historical knowledge. Newton has done a great job assembling a formidable bibliography1of both original sources and the works of respected historians, synthesizing them into an exposition of the forces responsible for the American experiment. Newton documents the disparate roles played by “angry mobs” and by “Founding Fathers.” These two forces were not always in sync with one another. At times the irascible mobs were in control, and the aristocratic Founders struggled to reign them in, guide their passions, or even just keep up. At other times, like during the period of Constitutional Convention, it was the Founders who struggled to convince the masses of the efficacy of their plans. The Founders learned to harness the power of a willful, independent people, and use it to ensure the success of the American experiment. But, at times they struggled to keep up with the enthusiasms and power of populism. Newton cites many of the books reviewed here at WWTFT, as well as many others. He is able to sift the salient points remarkably effectively in such a deceptively short volume. Newton explores the motivations of the “angry mobs” and Founding Fathers, from the colonial period, through the American Revolution, the failure of the Articles of Confederation, the Constitutional Convention, and Ratification. Newton clearly depicts the ebb and flow of power and participation between these two groups. He points out how, during the first part of the struggle for independence, it was the angry mobs more than the Founding Fathers, which drove the Revolution. In some sense, the angry mobs forced the issue. This is a thesis supported by writers like Gordon S. Wood, Harlow Giles Unger, T. H. Breen, and others. However, Mr. Newton explicitly details the ebb and flow of political force.  The “angry mobs” forced the issue and dragged the country into war with their precipitous actions. Once the country was involved, whether they liked it or not, the aristocratic Founders managed the effort with men like Washington. However, it was a precarious balance between the two forces as Alexander Hamilton wrote of the army in 1780,

It is now a mob, rather than an army; without clothing, without pay, without provision, without morals, without discipline. We begin to hate the country for its neglect of us. The country begin to hate us for our oppressions of them.  Congress have long been jealous of us. We have now lost all confidence in them, and give the worst construction to all they do. Held together by the slenderest of ties, we are ripening for a dissolution.

This ebb and flow of power continued to occur after the Revolution.

This ebb and flow of power continued to occur after the Revolution.

The angry mobs produced their revolution and succeeded to a limited extent. It would be up to the Founding Fathers, who had already done so much to ensure victory over the British and to maintain law and order, to create a working political system and secure peace and tranquility for generations to come.

But the tenuous balance of power between mob rule and stable government was precariously tilting towards anarchy under the Articles of Confederation. The Constitutional Convention was the remedy sought by those seeking stability.

Though the Founders saw the evils of mob rule, they also wished to harness its energy.  They wanted to turn the passions of the people into a supporter and protector of the new government instead of an enemy against it. Therefore, the Founding Fathers wanted to limit but not eliminate the democratic nature of their new government. They wanted to create a moderate government, one that balanced the rule of law with the democratic nature of the American people.

The Founders recognized that they needed a system of government based on the rule of law, for as John Adams said,

no man will contend, that a nation can be free, that is not governed by fixed laws. All other government than that of permanent known laws, is the government of mere will and pleasure, whether it be exercised by one, a few, or many.

In order to protect against tyranny, either of the few or majority, the Founders sought to build a bulwark of checks and balances in their new government. Madison famously lays this out in Federalist 51.

But the great security against a gradual concentration of the several powers in the same department, consists in giving to those who administer each department the necessary constitutional means and personal motives to resist encroachments of the others. The provision for defense must in this, as in all other cases, be made commensurate to the danger of attack. Ambition must be made to counteract ambition. The interest of the man must be connected with the constitutional rights of the place. It may be a reflection on human nature, that such devices should be necessary to control the abuses of government. But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself. A dependence on the people is, no doubt, the primary control on the government; but experience has taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions.

But Newton observes that the Founders recognized the need to go even farther in their quest to prevent tyranny. They recognized that ultimately, all power originates from the people and sought to ensure that this power was retained.

In the end, even with the systems of checks and balances, the Founding Fathers recognized that only people could prevent tyranny by the national or state governments. Alexander Hamilton wrote that if the Constitution is violated, “A remedy must be obtained from the people who can, by election of more faithful representatives, annul the acts of the usurpers.” If that fails, Madison describes other means: “If the representatives of the people betray their constituents, there is then no recourse left but in the exertion of the original right of self defense which is paramount to all positive forms of government… the citizens must rush tumultuously to arms, without concert, without system, without resource, except in their courage and despair.”

In spite of their own tyrannical nature, the power of the angry mobs provides the last bulwark against a tyrannical government. Or as Newton concludes:

Although Hamilton, Madison, and the Founding Fathers designed a Constitution that they hoped would make such actions unnecessary, they recognized that, in the end, the people are the “ultimate guardians of their own liberty.” [Thomas Jefferson]

In reading Newton’s book and contemplating this conclusion, this reviewer wondered for a moment how Hamilton, Madison, and the other Founders’ views could be assembled into one coherent conclusion. After all, the mob was an anathema to men like Hamilton, while Jefferson was all about watering the tree of liberty with the blood of patriots. However, although individually it might be difficult to reconcile the various quotes and views of the Founders, things that they expounded on at different points in their lives, collectively these men assembled the Constitution. This document was not the work of one man, but the result of compromise. Hamilton supported it as ardently as Madison. (Indeed, as Newton points out, Hamilton even borrowed some of Madison’s arguments, and even his very words at the New York Ratifying Convention.) If one looks at their views when forced through the filter of the Constitution and the Second, Ninth, and Tenth Amendments, the foundation of this conclusion becomes clear. Newton diverges a bit from his main theme in an interesting section on the creation of the Constitution and the philosophy behind the balance of power between the states and the federal government. He contends that in spite of their dissatisfaction with the status quo under the Articles of Confederation, the Founders still retained a healthy skepticism about investing too much power in the Federal government. Newton maintains that they intentionally vested more power in the state governments and supports his view with observations by de Tocqueville on the reality of this situation.

In reading Newton’s book and contemplating this conclusion, this reviewer wondered for a moment how Hamilton, Madison, and the other Founders’ views could be assembled into one coherent conclusion. After all, the mob was an anathema to men like Hamilton, while Jefferson was all about watering the tree of liberty with the blood of patriots. However, although individually it might be difficult to reconcile the various quotes and views of the Founders, things that they expounded on at different points in their lives, collectively these men assembled the Constitution. This document was not the work of one man, but the result of compromise. Hamilton supported it as ardently as Madison. (Indeed, as Newton points out, Hamilton even borrowed some of Madison’s arguments, and even his very words at the New York Ratifying Convention.) If one looks at their views when forced through the filter of the Constitution and the Second, Ninth, and Tenth Amendments, the foundation of this conclusion becomes clear. Newton diverges a bit from his main theme in an interesting section on the creation of the Constitution and the philosophy behind the balance of power between the states and the federal government. He contends that in spite of their dissatisfaction with the status quo under the Articles of Confederation, the Founders still retained a healthy skepticism about investing too much power in the Federal government. Newton maintains that they intentionally vested more power in the state governments and supports his view with observations by de Tocqueville on the reality of this situation.

State government remains the general rule, the federal government is the exception. … In America, real power resides in provincial government, rather more than in federal government. … The passions of the masses, and the provincial bias of every state still tend strangely to reduce the scope of federal power as it is laid down and to create pockets of resistance to its wishes.

Newton also points out,

The statistics also appear to confirm the relative weaknesses of the federal government. State and local government spending exceeded federal spending in most years until the 1940’s, except in war time. Based on this one metric, the state and local governments exerted more power than the federal government for about 150 years, except in the power to declare and make war.

To this reviewer, this is a sobering thought, indeed. With the advent of an entitlement state, we have shifted the balance of power from the states to the federal government by making the states beholden to the federal government. The federal government’s ability to withhold funding for education, infrastructure, medicare, and disaster recovery are but a few of the levers of power which have been willingly or unwillingly ceded to the federal government to the diminution of the states’ power. Newton crams quite a lot of information into this chapter, but returns to his theme indirectly by pointing out something of which most Americans are sadly unaware. The adoption of the Constitution was, in essence a new American Revolution. It changed the nation’s governance as completely as the first American Revolution did. However, the War of Independence was a war prosecuted largely through the will power of the “angry mobs” and cost many lives and much treasure.

Unlike the War for Independence, this revolution did not require years of fighting and thousands of deaths. It was accomplished by studying political philosophy, thoughtful deliberation, and compromise. James Wilson wrote, “After a period of 6000 years has elapsed since the creation, the United States exhibit to the world the first instance, as far as we can learn, of a nation, unattacked by external force, unconvulsed by domestic insurrections, assembling voluntarily, deliberating fully, and deciding calmly, concerning that system of government, under which they would wish that they and their posterity should live.”

It wasn’t the “angry mobs” that drove this second revolution, it was the Founders. This time it was the Founders that had to drag and cajole the people into agreement during the ratification conventions of the states. But the “angry mobs” were far from pacified after ratification. They continued to play a role in shaping the country’s policies. At times they reacted violently to the policies of their new government, in ways hearkening back to their response to British taxation.  When the new government put a tax whiskey, many farmers weren’t happy. Unlike Shay’s rebellion, the Whiskey Rebellion was put down in a measured but forceful way by a strong federal government. The government was able to deal with the angry mobs, albeit carefully. Although the Angry Mobs and Founding Fathers necessarily concludes with the time period shortly after ratification. The influence of the “angry mobs” continued during the War of 1812, the Civil War, the civil rights movement, and even today with the modern day Tea Parties. Then as now, their efforts benefit from the thoughtful consideration of the Founders. Newton concludes his book, saying as much:

Only by understanding the principles of the American Revolution set forth by the Declaration of Independence and following the system of government established by the Constitution can the American republic survive and flourish. Only by unifying the fierce spirit of the angry mobs with the prudence and wisdom of the Founding Fathers can the American people live in liberty, prosperity, and tranquility.

1.This reviewers list of books to read has now been expanded as a result of his tightly documented work!

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment