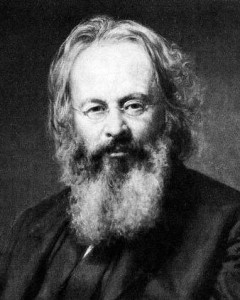

THE AMERICAN REPUBLIC: ITS CONSTITUTION, TENDENCIES, AND DESTINY by Orestes Augustus Brownson

This book was written at the end of the American Civil War, apparently finished sometime after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. It offers a commentary on the American experiment, an explanation of the reasons (right or wrong) that both the North and the South had for waging this war, and hope for the future. The author expresses that hope through a belief in the certain destiny of nations, in particular that of the United States

This book was written at the end of the American Civil War, apparently finished sometime after the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. It offers a commentary on the American experiment, an explanation of the reasons (right or wrong) that both the North and the South had for waging this war, and hope for the future. The author expresses that hope through a belief in the certain destiny of nations, in particular that of the United States

The United States, or the American Republic, has a mission, and is chosen of God for the realization of a great idea.

The first third of the book is devoted to an examination of America’s government. Brownson begins with the premise that nations are in some ways like people.

A nation has a spiritual as well as a material, a moral as well as a physical existence, and is subjected to internal as well as external conditions of health and virtue, greatness and grandeur, which it must in some measure understand and observe, or become weak and infirm, stunted in its growth, and end in premature decay and death.

And then explains

Among nations, no one has more need of full knowledge of itself than the United States, and no one has hitherto had less. It has hardly had a distinct consciousness of its own national existence, and has lived the irreflective life of the child, with no severe trial, till the recent rebellion, to throw it back on itself and compel it to reflect on its own constitution, its own separate existence, individuality, tendencies, and end.1

In Brownson’s view, America occupies a unique place in world history, in that the very idea behind it is liberty, but liberty tempered with the rule of law.

Its idea is liberty, indeed, but liberty with law, and law with liberty. Yet its mission is not so much the realization of liberty as the realization of the true idea of the state, which secures at once the authority of the public and the freedom of the individual—the sovereignty of the people without social despotism, and individual freedom without anarchy.

It is this concept that has given birth to perhaps the world’s best implementation of what is called the state.

The Greek and Roman republics asserted the state to the detriment of individual freedom; modern republics either do the same, or assert individual freedom to the detriment of the state. The American republic has been instituted by Providence to realize the freedom of each with advantage to the other.Â

Brownson goes on to explain the unique nature of America. In his view, while the United States took the best of the classic forms, it was not a mere combination of them, but something entirely new. Unfortunately, this fact is but dimly understood, even by those in government.

The originality of the American constitution has been overlooked by the great majority even of our own statesmen, who seek to explain it by analogies borrowed from the constitutions of other states rather than by a profound study of its own principles. They have taken too low a view of it, and have rarely, if ever, appreciated its distinctive and peculiar merits.

Later he expands on this,

The American system, wherever practicable, is better than monarchy, better than aristocracy, better than simple democracy, better than any possible combination of these several forms, because it accords more nearly with the principles of things, the real order of the universe. Emphasis WWTFT

The author goes on to postulate that this fundamental lack of understanding exacerbated, if not caused the American Civil War. The solution to the problems faced by America, North and South, was available to them in the Constitution, had they the wisdom to see it. While the issue of slavery was an enormous factor in precipitating the war, slavery was not the fundamental issue,

There is no doubt that the question of Slavery had much to do with the rebellion, but it was not its sole cause. The real cause must be sought in the program that had been made, especially in the States themselves, in forming and administering their respective governments, as well as the General government, in accordance with political theories borrowed from European speculators on government, the so-called Liberals and Revolutionists, which have and can have no legitimate application in the United States.

From here Brownson shows what the Constitution is and how it has been misunderstood.

… American statesmen have studied the constitutions of other states more than that of their own, and have succeeded in obscuring the American system in the minds of the people, and giving them in its place pure and simple democracy, which is its false development or corruption.2

Thus, from the very beginning of the book Brownson begins developing his thesis in a series of complex arguments which become steadily clearer when taken in totality. Brownson takes exception with many concepts assumed by many on the right to be settled and immutable. One of these is the notion that the United States governs at the consent of the governed. This belief was what Brownson later refers to as the egoism of the South.

With respect to the Southern states, Brownson felt that it was the egoism which led them to accept what amounted to mob rule. 3

… removing all obstacles to the irresponsible will of the majority, leaving minorities and individuals at their mercy.

It is interesting to reflect on this notion as most people probably do not think of the ante-bellum South as overly democratic. However, the fact of the matter is, in all cases, the populations of these states voted en masse for secession. This, despite the fact that the majority of people voting did not own slaves. They were instead, convinced of the justness their cause – the precedence of their home state over that of the federal government. Robert E. Lee himself is a good example of this, viewing himself as Virginian first and United States citizen second. Although he did not want secession, he felt his place was defending his state.

It is at this point that Brownson begins an examination of government, what it is, and what it means. This starts with society.

He (man) is born and lives in society, and can be born and live nowhere else. It is one of the necessities of his nature.

…

But society never does and never can exist without government of some sort. As society is a necessity of man’s nature, so is government a necessity of society.

And government implies hierarchy, as in a family there is a hierarchy. Anyone who has raised children knows this to be true. But Brownson explains that government is necessary not only to moderate the baser instincts of human beings, but also has a positive purpose.

Its office is positive as well as negative. It is needed to render effective the solidarity of the individuals of a nation, and to render the nation an organism, not a mere organization—to combine men in one living body, and to strengthen all with the strength of each, and each with the strength of all—to develop, strengthen, and sustain individual liberty, and to utilize and direct it to the promotion of the common weal—to be a social providence, imitating in its order and degree the action of the divine providence itself, and, while it provides for the common good of all, to protect each, the lowest and meanest, with the whole force and majesty of society.

Here Brownson begins his explanation of the hierarchy essential to government. It is a philosophical and logical argument touching on both the need and legitimacy of government.

To govern is to direct, control, restrain, as the pilot controls and directs his ship. It necessarily implies two terms, governor and governed, and a real distinction between them.

In other words, someone has to be in control.

To make the controller and the controlled the same is precisely to deny all control. There must, then, if there is government at all, be a power, force, or will that governs, distinct from that which is governed.

Government implies force, but a force that is used legitimately because of the authority inherent in the government.

Government is not only that which governs, but that which has the right or authority to govern. Power without right is not government.

The other side of this equation, if government is legitimate in its exercise of power, is the legitimacy and necessity for obedience to it.

The right to govern and the duty to obey are correlatives, and the one cannot exist or be conceived without the other. Hence loyalty is not simply an amiable sentiment but a duty, a moral virtue.

To comprehend the legitimacy of this situation, Brownson devotes a chapter to explaining the various theories on the origin of government, stating first that,

Government is both a fact and a right. Its origin as a fact, is simply a question of history; its origin as a right or authority to govern, is a question of ethics.

Brownson lists and examines seven such theories, dissecting them individually and elucidating on the merits and demerits of each argument. Unfortunately these arguments are too lengthy to explain thoroughly in this overview, but it would be difficult to continue without looking at a few, however superficially. One such is the concept of property as the basis of authority.

Property, ownership, dominion rests on creation. The maker has the right to the thing made. He, so far as he is sole creator, is sole proprietor, and may do what he will with it. God is sovereign lord and proprietor of the universe because He is its sole creator. He hath the absolute dominion, because He is absolute maker. He has made it, He owns it; and one may do what he will with his own. His dominion is absolute, because He is absolute creator, and He rightly governs as absolute and universal lord; yet is He is no despot, because He exercises only His sovereign right, and His own essential wisdom, goodness, justness, rectitude, and immutability, are the highest of all conceivable guaranties that His exercise of His power will always be right, wise, just, and good. The despot is a man attempting to be God upon earth, and to exercise a usurped power. Emphasis WWTFT

Brownson continues this logic to examine the supposed absolute right of parents over their children and shows that this does not in fact follow.

The right of the father over his child is an imperfect right, for he is the generator, not the creator of his child.

… in all Christian nations the authority of the father is treated, like all power, as a trust. The child, like the father himself, belongs to the state, and to the state the father is answerable for the use he makes of his authority. The law fixes the age of majority, when the child is completely emancipated; and even during his nonage, takes him from the father and places him under guardians, in case the father is incompetent to fulfill or grossly abuses his trust. This is proper, because society contributes to the life of the child, and has a right as well as an interest in him.

The key point here is that a parent is given a trust to exercise authority over his child, but that that trust is subject at some point to a higher authority, and that authority is the state, which itself is ultimately an expression of the divine order.

Brownson also dives into the concept of natural law and argues that it is an abstraction that doesn’t really exist outside of the mind of its creator.

The advocates of the theory deceive themselves by transporting into their imaginary state of nature the views, habits, and capacities of the civilized man.

…

Men are little moved by mere reasoning, however clear and convincing it may be. They are moved by their affections, passions, instincts, and habits. Routine is more powerful with them than logic. A few are greedy of novelties, and are always for trying experiments; but the great body of the people of all nations have an invincible repugnance to abandon what they know for what they know not.

It is here that Brownson takes on Jefferson and the notion of “consent of the governed.â€

This consent, as the matter is one of life and death, must be free, deliberate, formal, explicit, not simply an assumed, implied, or constructive consent. It must be given personally, and not by one for another without his express authority.

He goes on to explain that in practice this is impossible. Too many people have no choice in where they live. Their silence cannot be taken as tacit assent if they have no other choice than to leave, and leaving is not possible.

Furthermore, Brownson argues that provisional consent to be governed cannot work.

… if the government derives its powers from the consent of the governed, he governs in the government, and parts with none of his original sovereignty. The government is not his master, but his agent, as the principal only delegates, not surrenders, his rights and powers to the agent. He is free at any time he pleases to recall the powers he has delegated, to give new instructions, or to dismiss him.

…

Secession is perfectly legitimate if government is simply a contract between equals. The disaffected, the criminal, the thief the government would send to prison, or the murderer it would hang, would be very likely to revoke his consent, and to secede from the state.

Brownson continues with an argument that should resonate today.

The doctrine that one generation has no power to bind its successor is not only a logical conclusion from the theory that governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed, since a generation cannot give its consent before it is born, but is very convenient for a nation that has contracted a large national debt; yet, perhaps, not so convenient to the public creditor, since the new generation may take it into its head not to assume or discharge the obligations of its predecessor, but to repudiate them. No man, certainly, can contract for any one but himself; and how then can the son be bound, without his own personal or individual consent, …

Brownson concludes his discussion of natural law and the social compact,

… no civilized government ever did or could originate in the so-called social compact.

He also has some choice words about socialism.

He also has some choice words about socialism.

This new theory transfers to society the sovereignty which that asserted for the individual, and asserts social despotism, or the absolutism of the state. It asserts with sufficient energy public authority, or the right of the people to govern; but it leaves no space for individual rights, which society must recognize, respect, and protect.

On the other hand, a belief in the ultimate sovereignty of the individual, while derived from Christianity.

The doctrine of individual freedom before the state is due to the Christian religion, which asserts the dignity and worth of every human soul, the accountability to God of each man for himself, and lays it down as law for every one that God is to be obeyed rather than men.

When taken to extremes, individual sovereignty ignores the authority inherent in society and government. Hence, socialism and individualism are at odds with one another.

Individualism and socialism are each opposed to the other, and each has only a partial truth. The state founded on either cannot stand, and society will only alternate between the two extremes. Â

Brownson has some interesting observations on the theory that governments arose spontaneously as a development of nature. His insights into the hubris of scientists is as applicable today as it was 150 years ago.

Science explains the laws and conditions of the development, but disdains to ask for its origin or ground in any order that transcends the changes of the world of space and time. These philosophers profess to eschew all theory, and yet they only oppose theory to theory. The assertion that reality for the human mind is restricted to the positive facts of the sensible order, is purely theoretic, and is any thing but a positive fact. Principles are as really objects of science as facts, and it is only in the light of principles that facts themselves are intelligible. If the human mind had no science of reality that transcends the sensible order, or the positive fact, it could have no science at all. As things exist only in their principles or causes, so can they be known only in their principles and causes; for things can be known only as they are, or as they really exist. The science that pretends to deduce principles from particular facts, or to rise from the fact by way of reasoning to an order that transcends facts, and in which facts have their origin, is undoubtedly chimerical, and as against that the positivists are unquestionably right. But to maintain that man has no intelligence of any thing beyond the fact, no intuition or intellectual apprehension of its principle or cause, is equally chimerical. The human mind cannot have all science, but it has real science as far as it goes, and real science is the knowledge of things as they are, not as they are not. Sensible facts are not intelligible by themselves, because they do not exist by themselves; and if the human mind could not penetrate beyond the individual fact, beyond the mimetic to the methexic, or transcendental principle, copied or imitated by the individual fact, it could never know the fact itself. The error of modern philosophers, or philosopherlings, is in supposing the principle is deduced or inferred from the fact, and in denying that the human mind has direct and immediate intuition of it.

Brownson concludes his analysis of government by asserting that

Written constitutions alone will avail little, for they emanate from the people, who can disregard them, if they choose, and alter or revoke them at will. The reliance for the wisdom and justice of the state must after all be on moral guaranties.

Only a government based on moral principle – not a theocracy – but a government that fosters the same principles of morality as Christianity, can be successful. For it is this that works in concert with the natural order of things under moral laws that transcend human institutions.

Religion sustains the state, not because it externally commands us to obey the higher powers, or to be submissive to the powers that be, not because it trains the people to habits of obedience, and teaches them to be resigned and patient under the grossest abuses of power, but because it and the state are in the same order, and inseparable, though distinct, parts of one and the same whole. The church and the state, as corporations or external governing bodies, are indeed separate in their spheres, and the church does not absorb the state, nor does the state the church; but both are from God, and both work to the same end, and when each is rightly understood there is no antithesis or antagonism between them.

He warns,

Let the mass of the people in any nation lapse into the ignorance and barbarism of atheism, or lose themselves in that supreme sophism called pantheism, the grand error of ancient as well as of modern gentilism, and liberty, social or political, except that wild kind of liberty, and perhaps not even that should be excepted, which obtains among savages, would be lost and irrecoverable.

After finishing his discussion of the origins of government and its legitimacy, Brownson explains what a constitution is. This, at least, can be summed up briefly!

Basically, a constitution is comprised not only of the system of laws a nation gives itself, but more significantly of the people who live in it. This is a constitution in the sense that a body has a constitution. If you say that Joe has the constitution of an ox, it means that he is strongly put together and exudes health. It is in similar vein that Brownson uses the term. The constitution of a nation lies in the character of a nation and it’s people.

There must, then, be for every state or nation a constitution anterior to the constitution which the nation gives itself, and from which the one it gives itself derives all its vitality and legal force.

…

The constitution is the intrinsic or inherent and actual constitution of the people or political community itself; that which makes the nation what it is, and distinguishes it from every other nation, and varies as nations themselves vary from one another.

Af first the reader might wonder why Brownson goes to the lengths he does to make this distinction. However, it soon becomes evident. It is the basis for his arguments on sovereignty. Remember that this book was written in the context of the Civil War. Brownson lays out an argument that America was in fact a nation, even before the Revolution because sovereignty is wrapped up in the character of the people and closely tied to the territory that they occupy. Hence, in his view, the states never truly existed as sovereign entities prior to the American Revolution, and after, even under the Articles of Confederation, they had jointly worked to secure the sovereignty of The United States, rather than that of the individual states.

Certain it is that the States in the American Union have never existed and acted as severally sovereign states. Prior to independence, they were colonies under the sovereignty of Great Britain, and since independence they have existed and acted only as states united. The colonists, before separation and independence, were British subjects, and whatever rights the colonies had they held by charter or concession from the British crown. The colonists never pretended to be other than British subjects, and the alleged ground of their complaint against the mother country was not that she had violated their natural rights as men, but their rights as British subjects—rights, as contended by the colonists, secured by the English constitution to all Englishmen or British subjects. Â

In the Declaration of Independence they declared themselves independent states indeed, but not severally independent. The declaration was not made by the states severally, but by the states jointly, as the United States. They unitedly declared their independence; they carried on the war for independence, won it, and were acknowledged by foreign powers and by the mother country as the United States, not as severally independent sovereign states. Severally they have never exercised the full powers of sovereign states; they have had no flag—symbol of sovereignty—recognized by foreign powers, have made no foreign treaties, held no foreign relations, had no commerce foreign or interstate, coined no money, entered into no alliances or confederacies with foreign states or with one another, and in several respects have been more restricted in their powers in the Union than they were as British colonies.

This is obviously germane to the argument over whether or not the Southern states had the right to secede.

Brownson spends a good deal more time on this argument than this, but hopefully this is a clear if inadequate summary.

After making these arguments, Brownson devotes some time to the nature of the unwritten constitution as well as the written constitution and the separation of powers between the States and the Federal government. In his view, they work in concert with one another with both having defined roles.

The General government is the complement of the State governments, and the State governments are the complement of the General government.

For purposes of brevity, we will skip that discussion in order to move on to the closing discussion undertaken by Brownson about Reconstruction and his analysis of what the war actually meant.

Brownson makes a distinction between civil rights and human rights. It is a violation of human rights to deprive someone of their liberty, however participation in the body politic is not necessarily a human right, given the precedence and authority of government. In his view,

… all civil rights of every sort created by the individual State are really held from the United States, and therefore it was that the people of non-slaveholding States were, as citizens of the United States, responsible for the existence of slavery in the States that seceded. There is a solidarity of States in the Union as there is of individuals in each of the States. The political error of the Abolitionists was not in calling upon the people of the United States to abolish slavery, but in calling upon them to abolish it through the General government, which had no jurisdiction in the case; or in their sole capacity as men, on purely humanitarian grounds, which were the abrogation of all government and civil society itself, instead of calling upon them to do it as the United States in convention assembled, or by an amendment to the constitution of the United States in the way ordained by that constitution itself.

….

General government can no more enfranchise than it can disfranchise any portion of the territorial people, and the question of negro suffrage must be left, where the constitution leaves it—to the States severally, each to dispose of it for itself. Negro suffrage will, no doubt, come in time, as soon as the freedmen are prepared for it, and the danger is that it will be attempted too soon.

…Â

Negro suffrage on the score of loyalty, is at best a matter of indifference to the Union, and as the elective franchise is not a natural right, but a civil trust, the friends of the negro should, for the present, be contented with securing him simply equal rights of person and property.

(The book was written before the 15th Amendment was ratified.)

The egoism referred to at the beginning of this review is covered here in Brownson’s explanation of the motivations of the Confederacy.

This is the so-called Jeffersonian democracy, in which government has no powers but such as it derives from the consent of the governed, and is personal democracy or pure individualism philosophically considered, pure egoism, which says, “I am God.”

…

The full realization of this tendency, which, happily, is impracticable save in theory, would be to render every man independent alike of every other man and of society, with full right and power to make his own will prevail.

…

This personal democracy has been signally defeated in the defeat of the late confederacy, and can hardly again become strong enough to be dangerous.

On the other side of the question:

At the North there has been, and is even yet, an opposite tendency—a tendency to exaggerate the social element, to overlook the territorial basis of the state, and to disregard the rights of individuals. This tendency has been and is strong in the people called abolitionists. The American abolitionist is so engrossed with the unity that he loses the solidarity of the race, which supposes unity of race and multiplicity of individuals; and falls to see any thing legitimate and authoritative in geographical divisions or territorial circumscriptions.

Were his socialistic tendency to become exclusive and realized, it would found in the name of humanity a complete social despotism, which, proving impracticable from its very generality, would break up in anarchy, in which might makes right, as in the slaveholder’s democracy. The abolitionists, in supporting themselves on humanity in its generality, regardless of individual and territorial rights, can recognize no state, no civil authority, and therefore are as much out of the order of civilization, and as much in that of barbarism, as is the slaveholder himself.

…

The abolitionists were right in opposing slavery, but not in demanding its abolition on humanitarian or socialistic grounds.

Most interestingly, Brownson explains that the war was really about two opposing forms of democracy, that which was based on territorial democracy – the North, and personal democracy – the South. Both sides’s positions were usurped by others seeking to claim the justification or victory.

It rarely happens that in any controversy, individual or national, the real issue is distinctly presented, or the precise question in debate is clearly and distinctly understood by either party. Slavery was only incidentally involved in the late war. The war was occasioned by the collision of two extreme parties; but it was itself a war between civilization and barbarism, primarily between the territorial democracy and the personal democracy, and in reality, on the part of the nation, as much a war against the socialism of the abolitionist as against the individualism of the slaveholder.

…

The socialistic democracy was enlisted by the territorial, not to strengthen the government at home, as it imagines, for that it did not do, and could not do, since the national instinct was even more opposed to it than to the personal democracy; but under its antislavery aspect, to soften the hostility of foreign powers, and ward off foreign intervention, which was seriously threatened.

A few pages earlier, Brownson remarked,

The great body of the loyal people instinctively felt that pure socialism is as incompatible with American democracy as pure individualism; and the abolitionists are well aware that slavery has been abolished, not for humanitarian or socialistic reasons but really for reasons of state, in order to save the territorial democracy.

Brownson concludes that, despite the costs, all Americans benefited from the outcome, because while the principle of territorial democratic sovereignty was resolved once and for all, this did not represent a victory for the socialists.

It is not socialism nor abolitionism that has won; nor is it the North that has conquered. The Union itself has won no victories over the South, and it is both historically and legally false to say that the South has been subjugated. The Union has preserved itself and American civilization, alike for North and South, East and West. The armies that so often met in the shock of battle were not drawn up respectively by the North and the South, but by two rival democracies, to decide which of the two should rule the future. They were the armies of two mutually antagonistic systems, and neither army was clearly and distinctly conscious of the cause for which it was shedding its blood; each obeyed instinctively a power stronger than itself, and which at best it but dimly discerned.

However, this did not keep the socialists from claiming victory, and Brownson offers a dire warning.

The humanitarians are more dangerous in principle than the egoists, for they have the appearance of building on a broader and deeper foundation, of being more Christian, more philosophic, more generous and philanthropic; but Satan is never more successful than under the guise of an angel of light. His favorite guise in modern times is that of philanthropy. He is a genuine humanitarian, and aims to persuade the world that humanitarianism is Christianity, and that man is God; that the soft and charming sentiment of philanthropy is real Christian charity; and he dupes both individuals and nations, and makes them do his work, when they believe they are earnestly and most successfully doing the work of God.

Brownson sees these so-called humanitarians for what they are.

The humanitarian is carried away by a vague generality, and loses men in humanity, sacrifices the rights of men in a vain endeavor to secure the rights of man, as your Calvinist or his brother Jansenist sacrifices the rights of nature in order to secure the freedom of grace. Â grace. Yesterday he agitated for the abolition of slavery, to-day he agitates for negro suffrage, negro equality, and announces that when he has secured that he will agitate for female suffrage and the equality of the sexes, forgetting or ignorant that the relation of equality subsists only between individuals of the same sex; that God made the man the head of the woman, and the woman for the man, not the man for the woman. Having obliterated all distinction of sex in politics, in social, industrial, and domestic arrangements, he must go farther, and agitate for equality of property. But since property, if recognized at all, will be unequally acquired and distributed, he must go farther still, and agitate for the total abolition of property, as an injustice, a grievous wrong, a theft, with M. Proudhon, or the Englishman Godwin. It is unjust that one should have what another wants, or even more than another. What right have you to ride in your coach or astride your spirited barb while I am forced to trudge on foot? Nor can our humanitarian stop there. Individuals are, and as long as there are individuals will be, unequal: some are handsomer and some are uglier, some wiser or sillier, more or less gifted, stronger or weaker, taller or shorter, stouter or thinner than others, and therefore some have natural advantages which others have not. There is inequality, therefore injustice, which can be remedied only by the abolition of all individualities, and the reduction of all individuals to the race, or humanity, man in general. He can find no limit to his agitation this side of vague generality, which is no reality, but a pure nullity, for he respects no territorial or individual circumscriptions, and must regard creation itself as a blunder. This is not fancy, for he has gone very nearly as far as it is here shown, if logical, he must go.

Philanthropy seldom works in private against private vices and evils: it is effective only against public grievances, and the farther they are from home and the less its right to interfere with them, the more in earnest and the more effective for evil does it become. Its nature is to mind every one’s business but its own.

….

The egoistical form is checked, sufficiently weakened by the defeat of the rebels; but the social form believes that it has triumphed, and that individuals are effaced in society, and the States in the Union.

In the final chapter of this book, Brownson returns to his original contention that the United States has a destiny.

But the United States have a religious as well as a political destiny, for religion and politics go together. Church and state, as governments, are separate indeed, but the principles on which the state is founded have their origin and ground in the spiritual order—in the principles revealed or affirmed by religion—and are inseparable from them. There is no state without God, any more than there is a church without Christ or the Incarnation.

There is a good deal to think about in this book and what it has to say will challenge the modern Right as well as Left. The former, depending on his religious beliefs, may be more inclined to give it due consideration, despite it’s challenging propositions. The latter are the very people that Brownson warned about, and will no doubt dismiss it as a religious rant, despite the clarity of Brownson’s arguments.

1. Reading these words, one has to wonder at the condition of the United States today with a generation of people who have lived “the irreflective life of a child, with no severe trial …â€

These gray-haired children have amassed enormous debts, both personally and for the country as a whole. Can this decision for instant gratification and the deferring of payment onto the backs of subsequent generations be seen as anything other than the product of immaturity, political selfishness, and irresponsibility?

2. The reviewer cannot bring himself to call John Kerry a statesman, but otherwise he and his ilk would seem to be exactly to what Brownson is referring.

3. Brownson does not reserve his criticism for the South alone. He suggests that many in the North suffered under an equally false delusion on the other side of the political spectrum, a belief in socialism – more on this later in the review.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment