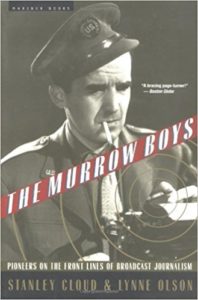

Review: The Murrow Boys: Pioneers on the Front Lines of Broadcast Journalism

The Murrow Boys: Pioneers on the Front Lines of Broadcast Journalism

By Stanley Cloud and Lynne Olson

This is an excellent book on many levels. The husband-and-wife team of Cloud (former Washington bureau chief for Time) and Olson (former Moscow correspondent for Associated Press) pierce the smog of time to recall The Murrow Boys. They were broadcast journalists who both reported history and made it. In an accompanying chronicle, the authors’ describe radio’s glory days, its decline, and its impact on American life.Â

In the 1920s, most people didn’t know what radio was. By 1930 many couldn’t imagine life without it. Radio provided entertainment at a time when diversion was especially welcome. Comedians like Eddie Cantor and Fred Allen made people laugh. Soap operas provided detours from the grim realities of life during Depression.

NBC had captured all the top entertainment stars from vaudeville and the concert halls. As a result they had a better sponsor’s list than CBS. William Paley at CBS hired Murrow as “European Director,†(booking agent for cultural events). He was sent abroad in 1937 to challenge NBC’s cultural dominance and disrupt NBC’s contract advantages. It was a cutthroat, highly competitive business.

Radio news, such as it was, was delivered by commentators who scanned the morning newspaper for material or picked it up from the wire services. Their task was to amuse and be controversial enough to attract listeners, but measured enough to avoid lawsuits or censorship. Being reporters was not part of their gig. Neither Paley at CBS nor David Sarnoff at NBC thought radio had a future in news. Neither station had any reporters traveling the globe for news. The corporate mantra was that news and analysis belonged to newspaper or wire service foreign correspondents. But that was before The Murrow Boys invented broadcast journalism.

‘We had to create it as we went along,’ Eric Sevareid once said. ‘There were no precedents. We had to create the tradition…’ There had never been a group of reporters quite like them before, and there never was again.Â

Finally, this book is relevant. The authors’ explain how the high standards of journalism, embodied by Murrow and his boys, devolved to what it is today. Television is part of that history, but more about that later.

Edward R. Murrow

Murrow’s real name was Egbert Roscoe Murrow. In He was born April 25, 1908 in Polecat Creek, North Carolina, The family was poor and Murrow learned the value of hard work early. By 15 he was driving a school bus. In high school and later at Washington State he worked summers as a lumberjack. He was  teased about his first name and (unofficially) changed it to Edward, and Edward it remained. In college he majored in speech and dabbled in acting and debating.

After graduation he worked as an organizer of student conferences in the United States and Europe. He went abroad three times and made some valuable contacts. He had come a long way from Polecat Creek.

Murrow was tall, lean, handsome and likable, and an astute judge of people and talent. He did not have any real journalism experience. He did have a wonderfully deep and compelling voice, perfect for radio.

Murrow Boys

William L. Shirer, an itinerant, out-of-work American newspaperman was the first Murrow boy. Murrow was 29 years old when he brought Shirer in as his assistant. Shirer came from an intellectually gifted but financially challenged family. Only four years older than Murrow, his sandy hair was already receding. He wore a small mustache and thick, metal-rimmed glasses. After a series of jobs, Shirer went to work for the Berlin office of Hearst’s Universal wire service. From 1934 to 1937 he became a highly respected foreign correspondent. Then Universal shut down and Shirer became an unemployed foreign correspondent.

William L. Shirer, an itinerant, out-of-work American newspaperman was the first Murrow boy. Murrow was 29 years old when he brought Shirer in as his assistant. Shirer came from an intellectually gifted but financially challenged family. Only four years older than Murrow, his sandy hair was already receding. He wore a small mustache and thick, metal-rimmed glasses. After a series of jobs, Shirer went to work for the Berlin office of Hearst’s Universal wire service. From 1934 to 1937 he became a highly respected foreign correspondent. Then Universal shut down and Shirer became an unemployed foreign correspondent.

He was exactly the man Murrow sought. CBS, however, insisted on a test to determine if Shirer’s voice was suitable for radio. German broadcasting studios were under contract with NBC and not available to CBS. They had to improvise. Murrow assured an anxious Shirer he’d have a microphone and everything he needed.

Ten days later, practically paralyzed with nervousness, Shirer reported to a dingy room strewn with packing boxes in the government telegraph office in Berlin.

The microphone hung from a boom seven feet above the floor and stubbornly refused to be lowered. Â

Shirer frantically pulled over a piano packing crate, and the engineer boosted Shirer up onto it. Sitting on that rough wooden crate, with his feet dangling in the air like a ventriloquist’s dummy’s, trying desperately to remember the points Murrow had made about speaking over the air, Shirer fought back the impulse to burst out in hysterical laughter.

His voice, thin and reedy at best, quavered and tended to jump an octave as his nervousness progressed. Shirer was terrible and CBS refused to hire him. Murrow persisted and eventually prevailed. Shirer never lost his nervousness about radio.

Identifying all the Morrow boys was difficult for Cloud and Olson. Murrow worked with many journalists over the years, but to make the cut one had to be hired by Murrow and have stayed to the end of hostilities. Although there were a few exceptions to these criteria, there is no question that everyone listed below qualified. Â

In alphabetical order they are: Mary Marvin Breckinridge, Cecil Brown, Winston Burdett, Charles Collingwood, William Olson Downs, Thomas Grandin, Richard C. Hottelet, Larry LeSueur, Eric Sevareid, William L. Shirer, and Howard K. Smith…

The names were confirmed during extensive interviews with Murrow’s widow, Janet. The authors write, ‘for us that settled the matter…

…’There are no imaginary conversations or scenes, nothing that goes beyond the facts as developed in archival research, extensive reading, listening to old broadcasts, and scores of interviews, including many with the surviving Boys… This is a wholly factual account of how legends are born and dreams die…   Â

World-shaking events were taking place in Europe, but CBS refused to permit Murrow and Shirer to broadcast them. As far as New York was concerned, the threat of war in Europe did not in any way alter Murrow’s job description and that of his assistant. They were hired to arrange cultural broadcasts and to overcome NBC’s advantages abroad – discussion closed.Â

On March 9, the Austrian government, desperate to save itself from Hitler, announced a popular vote on the nation’s future, to be held four days later. At CBS, a children’s choir in Belgrade took precedence. Shirer was dispatched to arrange for the event.Â

This was the biggest story of Shirer’s life. Austria was about to be swallowed by Germany. The devil take NBC, Shirer was going to Berlin. Or so he thought. Men in Nazi uniforms, brandishing revolvers for emphasis, threw Shirer out of the German broadcasting studio. A distraught Shirer returned to his apartment and Ed Murrow called from London.

He told Shirer to get on a plane to London. As soon as he arrived, he could go on the air and give the first uncensored account. ‘Don’t let them tell you you’re not supposed to talk,’ Murrow said. ‘Just go on, and I’m going to go on, too.’

Seventeen hours later Shirer was sitting in a British Broadcasting Corporation studio in London, earphones on, listening to the CBS announcer in New York say, ‘We take you now to London.’

Murrow was in Vienna covering for Shirer. They were not only going to finally report the news, they were going to be first with a major story. NBC, however, had a counterpart to Murrow in Germany similarly intent on breaking the story and his German contacts were better. He scooped CBS while Shirer was still traveling.

In New York, Paley was desperate to trump NBC. He had the CBS news department phone Shirer these instructions: He was to broadcast a European roundup that night, a thirty-minute broadcast on European reaction to the Anschluss. It was to consist of interviews with a Member of Parliament in London, Murrow in Vienna, and American newspaper correspondents in Paris, Berlin, and Rome.

CBS was finally going to let them broadcast. Shirer and Murrow had eight hours to pull it all together. Saying no was not an option.

Never mind that no one had ever done it. Never mind that it was five o’clock, London time, on a Sunday afternoon, which meant that all offices were closed and that all the technicians and correspondents and members of Parliament they would need were out of town, off in the country, or otherwise unreachable. Never mind the seemingly insuperable technical problems of arranging the lines and transmitters, of ensuring the necessary split-second timing. Never mind any of that.

Shirer called Murrow and they got to work. Calls in four languages streamed to Shirer in London. Somehow, they contacted all the people they needed. How they accomplished it is absorbing reading.

Finally, on March 13, at 1 A.M. London time, 8 P.M. in New York, an exhausted Shirer put on his earphones and heard announcer Bob Trout say, ‘The program ‘St. Louis Blues’ will not be heard tonight.’ In its place would be a special report, a ‘radio tour of Europe’s capitals, starting with a transoceanic pickup from London.’ Trout paused. ‘We take you now to London.’ And Shirer was on.

Adrenaline overcame fatigue, Shirer’s soft, flat voice did not betray either his excitement or the pressure he was under. He was professional. He was calm. There was no hint that he knew he was making broadcast history with the first CBS News Roundup.

CBS was triumphant and ordered another Roundup for the next night. CBS and radio in general were on their way to becoming full-fledged news sources.

Shirer and Murrow had proven that radio was not only able to report news as it occurred, but put it in context to link with news from elsewhere — and do all that with unprecedented speed and immediacy.

Not easy under the best of circumstances. Radio after all, was in its technological infancy. In addition to the vicissitudes of wartime, they had to cope with fidelity- destroying shortwave whine, stutter and crackle plus interference from weather and sunspots. Some of the best reporting was lost in the ether. Yet, they put in motion a chain of events that would lead, in only one year, to radio’s emergence as America’s chief news medium and the beginning of CBS’s decades-long dominance of broadcast journalism.  Â

For Murrow and Shirer, elation soon gave way to exhaustion as they tried to deliver European war news from everywhere it was happening. They needed reinforcements.

Murrow hired Thomas Grandin, an Ivy League intellectual with no journalistic experience. When CBS Director of News Paul White heard Grandin’s voice he was appalled. Again, Murrow prevailed. Talent, intelligence, and knowledge were always more important to Murrow than credentials or radio voice. In the spring of 1939 Murrow installed Grandin in Paris.

Next Murrow called Eric Sevareid in Paris. Sevareid, twenty-six years old at the time and only three years out of college was married, broke and holding down two jobs as a daytime reporter and editor for the Paris Herald earning twenty-five dollars a week. This native of the North Dakota prairie was handsome, tall and rugged-looking and could ‘write like an angel.’ Â

Sevareid’s voice was New York’s worst nightmare. It didn’t matter. One day after being hired (August 23, 1939), Hitler and Stalin announced their non-aggression pact. Sevareid rushed to Paris to help Tom Grandin. Â

Within a week after Germany invaded Poland direct communications between England and Germany were cut off. Except for what Shirer could pick up from other correspondents and diplomatic sources, what he received from Germany was more Nazi propaganda than news.Â

In America, President Roosevelt had reaffirmed the nation’s neutrality. Broadcast news was directed to say nothing that might cause Americans to question that policy. If American intervention became necessary, Roosevelt wanted to control the process. FDR’s press secretary Steve Early warned the networks to behave or suffer consequences. CBS quickly imposed strict objectivity.Â

Objectivity was part of Murrrow’s creed as a journalist, but the word was Orwellian when CBS used it to mandate fake news. Shirer utilized irony and insinuation to get around Nazi censorship and network “objectivity.“ American slang expressions, unfamiliar to German censors, challenged Nazi versions of events. Murrow and the others developed other creative evasions to convey skepticism. New York was not happy.

The foregoing is a sample of what readers can expect from Cloud and Olson. Space does not permit an exposition on every Murrow boy (one was a girl who reported from various war zones for almost a year before CBS enforced its no  women broadcasters rule). Suffice it to say that the authors do an excellent job of weaving the boys’ backgrounds, personalities, wartime escapades, reporting prowess and post war lives into the narrative.Â

Television

Murrow persuaded the boys who were still with CBS when the war ended — Eric Sevareid, Larry LeSueur, Charles Collingwood, Winston Burdett, Howard K. Smith, Bill Downs, Richard C. Hottelet, and William L. Shirer —to stay.Â

His wanted to make sure CBS would put them in meaningful positions. Â

They were celebrities when they returned to America, remembered and admired for their reporting and their courage. Some wrote critically acclaimed books (Shirer’s Berlin Diary, Smith’s Last Train From Berlin). They were in demand for interviews and public appearances. CBS was happy to capitalize on their success.

Between 1948 and 1951 the nation was transformed. Radio, in its pre-fifties guise, was dead. Ed Murrow and the Boys were forced to adjust to television, which they detested. Murrow laid down conditions that established a standard of excellence by which to measure TV news.Â

But some TV executives saw them simply as Luddites. Commercial success changed the networks and to some extent the Murrow boys. Their relationship with CBS, never an easy one, became more fraught. Sensationalism and the wishes of corporate sponsors gradually eroded the Murrow standard. The Intellectual content that distinguished the wartime coverage and had defined CBS faded away and with it the value Murrow and his boys had for CBS. For Paley, it was all about ratings and sponsors. Â Â

It was well and good to have Murrow and this big news organization that everyone respected, but news didn’t generate enough revenue in a peacetime economy and probably never would. Without the drama of a world at war, there simply wasn’t that much demand for news.Â

Television diminished radio and repeated history by reshaping America. All of the attributes that Murrow prized in his boys lost currency. The new medium was, almost by definition, superficial. It had little memory, little sense of history, little to no appreciation of context, and sparse interest in hard news. News anchors were chosen for their looks and charm and often did not personally cover stories. That became the norm.Â

In short, commercial television –In the days when it was limited to over-the-air broadcasts and before it had metastasized into various cable and on-line news and talk shows – -trivialized and corrupted what Murrow and his boys did, then grew tired of them and tossed them aside…

Epilog

In January 1961 the great Edward R. Murrow-CBS epic — which had begun in 1935 and swept through World War II, the postwar era, the Cold War, the advent of television, and McCarthyism — ended. Murrow accepted an offer from President-elect John Kennedy to become director of the United States Information Agency — “a beautiful and timely gift,†said Janet Murrow

Perhaps, given the dynamics of television, there could have been no other result.Â

They were among the best of their generation yet also typical of it. For they were American to the core, no matter what part of the country they sprang from. In their day their influence was enormous. But their true medium was radio, and their day was short.

According to former CBS colleague, Charles Kuralt:

“They brought a tone of scholarship. They knew their subjects and they were able to refer easily to the past and draw conclusions for the present… I think you can safely say there’s no one like that in broadcasting today.

This reviewer would go further and say few mainstream journalists, whether print or broadcast, subscribe to the code by which the Murrow Boys lived. They were, to the best of their abilities, truth-tellers. They believed that journalists had a duty to provide the public with the information they need to make the best decisions about their lives and communities.

This reviewer would go further and say few mainstream journalists, whether print or broadcast, subscribe to the code by which the Murrow Boys lived. They were, to the best of their abilities, truth-tellers. They believed that journalists had a duty to provide the public with the information they need to make the best decisions about their lives and communities.

A different premise guides journalism today and is taught in many J schools. As defined by Wikipedia, Advocacy Journalism “adopts a non-objective viewpoint, usually for some social or political purpose.†This effluent of egoism holds that rule by experts is preferable to citizens making their own decisions and that reporters should determine which social or political purpose prevails.

Barack Obama’s former Deputy National Security Advisor for Strategic Communications, Ben Rhodes (unintentionally) described how advocacy journalism works. (This euphemistic job description might have challenged even George Orwell’s creative imagination.) Rhodes bragged how he and other spinners created an “echo chamber†to support the President’s Iran deal.

‘All the newspapers used to have foreign bureaus,’ he said. “Now they don’t.  They call us to find out what’s happening in Moscow and Cairo. The average reporter we talk to is 27 years old, and their only reporting experience consists of political campaigns. That is a sea change. They literally know nothing.

Rhodes was contemptuous of the Washington policy and media establishment, including The Washington Post and the New York Times. He referred to them as “the blob†that is subject to “conventional thinking.â€

If by conventional thinking Rhodes meant the prevailing ideological biases, he is correct. He is correct also about reporters’ abysmal knowledge deficits. If that is true, it follows that they have little to think about. Certainly, regard for self-preservation would indicate that staying within the echo chamber is the better part of valor.Â

Other examples of Media bias abound. Think Obama Care, climate change, experiments in sexual behavior. All supported by government “experts.†News or views not in accord get neither ink nor airtime.

The result, according to opinion polls, is a 20-year decline in pubic trust. When asked if they trust the mass media “to report the news fully, accurately and fairly” only 32% respondents said, “they have a great deal or fair amount of trust in the media.†(Gallop 2017)

Apparently, 68% still believe in truth, accuracy, fairness and impartiality.

For now.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment