Principles Make Strange Bedfellows …

Who would have ever thought Justices Antonin Scalia, Ruth Bader Ginsberg, Elena Kagan, and Sonia Sotomayor would share an opinion on the court. Yet this group formed the dissenting opinion in the controversial DNA testing case recently ruled on by the Supreme Court. But, then again, whoever thought that WWTFT would sing the praises of an article written in the New Republic .. strange times indeed. This from an excellent piece by Jeffrey Rosen:

Some of Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia’s greatest opinions have involved his passionate defense of the Fourth Amendment right against unreasonable searches and seizures. It was Scalia who held, for a majority of the Court, that police need a valid warrant before they can use thermal imaging devices on a suspect’s home, or track his movements 24/7 for a month using a GPS device. Scalia has also written memorable dissents in defense of privacy, including his denunciation of warrantless drug testing for customs employees as “a kind of immolation of privacy and human dignity in symbolic opposition to drug use.â€

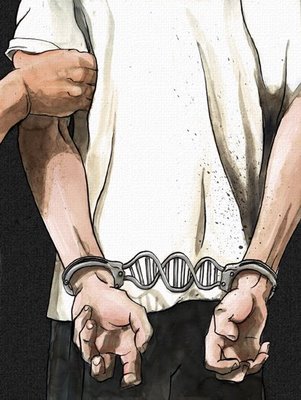

Yesterday, Scalia added to this impressive list by writing not only one of his own best Fourth Amendment dissents, but one of the best Fourth Amendments dissents, ever. In a 5-4 decision written by Justice Anthony Kennedy, who was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and justices Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas, and Stephen Breyer (who often sides with the conservatives in Fourth Amendment cases), the Court upheld Maryland’s DNA Collection Act. That law allows the police to seize DNA without a warrant from people who have been arrested for serious crimes and then plug the sample into the federal CODIS database, to see if they are wanted for unrelated crimes. Scalia’s dissent (starting at page 33) is indeed eloquent:

Yesterday, Scalia added to this impressive list by writing not only one of his own best Fourth Amendment dissents, but one of the best Fourth Amendments dissents, ever. In a 5-4 decision written by Justice Anthony Kennedy, who was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and justices Samuel Alito, Clarence Thomas, and Stephen Breyer (who often sides with the conservatives in Fourth Amendment cases), the Court upheld Maryland’s DNA Collection Act. That law allows the police to seize DNA without a warrant from people who have been arrested for serious crimes and then plug the sample into the federal CODIS database, to see if they are wanted for unrelated crimes. Scalia’s dissent (starting at page 33) is indeed eloquent:

The Fourth Amendment forbids searching a person for evidence of a crime when there is no basis for believing the person is guilty of the crime or is in possession of incriminating evidence. That prohibition is categorical and without exception; it lies at the very heart of the Fourth Amendment. Whenever this Court has allowed a suspicionless search, it has insisted upon a justifying motive apart from the investigation of crime.

Where do we draw the line? Can the authorities simply decide to go on a fishing expedition and molest any citizen on the pretense that they “might” be guilty of something? This is not farfetched. The framers of the Bill of Rights weren’t content to let the Constitution stand without explicit prohibitions on unreasonable searches and seizures.  The Fourth Amendment states pretty plainly:

The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by Oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.

Initially, Madison, who is sometimes referred to as the father of the Constitution, did not see the need for a Bill of Rights as he contended that the Constitution was one of enumerated powers and that which was not explicitly delegated to the government was, of course, forbidden to it.

However, he came around, and shepherded the Bill of Rights through the first Congress, even after some of the impetus and political pressure to do so had abated. Scalia explains why.

At the time of the Founding, Americans despised the British use of so-called “general warrantsâ€â€”warrants not grounded upon a sworn oath of a specific infraction by a particular individual, and thus not limited in scope and application. The first Virginia Constitution declared that “general warrants, whereby any officer or messenger may be commanded to search suspected places without evidence of a fact committed,†or to search a person “whose offence is not particularly described and supported by evidence,†“are grievous and oppressive, and ought not be granted.†Va. Declaration of Rights §10 (1776), in 1 B. Schwartz, The Bill of Rights: A Documentary History 234,235 (1971). The Maryland Declaration of Rights similarly provided that general warrants were “illegal.†Md. Declaration of Rights §XXIII (1776), in id., at 280, 282.

In the ratification debates, Antifederalists sarcastically predicted that the general, suspicionless warrant would be among the Constitution’s “blessings.†Blessings of the New Government, Independent Gazetteer, Oct. 6, 1787, in 13 Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution 345 (J. Kaminski & G. Saladino eds. 1981). “Brutus†of New York asked why the Federal Constitution contained no provision like Maryland’s, Brutus II, N. Y. Journal, Nov. 1, 1787, in id., at 524, and Patrick Henry warned that the new Federal Constitution would expose the citizenry to searches and seizures “in the most arbitrary manner, without any evidence or reason.†3 Debates on the Federal Constitution 588 (J. Elliot 2d ed. 1854). Madison’s draft of what became the Fourth Amendment answered these charges by providing that the “rights of the people to be secured in their persons . . . from all unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated by warrants issued without probable cause . . . or not particularly describing the places to be searched.†1 Annals of Cong. 434–435 (1789). As ratified, the Fourth Amendment’s Warrant Clause forbids a warrant to “issue†except “upon probable cause,†and requires that it be “particula[r]†(which is to say, individualized) to “the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.†And we have held that, even when a warrant is not constitutionally necessary, the Fourth Amendment’s general prohibition of “unreasonable†searches imports the same requirement of individualized suspicion.

But Scalia doesn’t stop with explaining the reasons for the Fourth Amendment. He rips into the majority’s weak justifications for the ruling with biting logic. The real reason for the DNA swabs is to help the police solve other crimes for which they have DNA evidence.  But solving cold cases is not a good justification for throwing the Fourth Amendment out the window.

The Court’s assertion that DNA is being taken, not to solve crimes, but to identify those in the State’s custody, taxes the credulity of the credulous.

…

The Court hastens to clarify that it does not mean to approve invasive surgery on arrestees or warrantless searches of their homes. … That the Court feels the need to disclaim these consequences is as damning a criticism of its suspicionless-search regime as any I can muster. And the Court’s attempt to distinguish those hypothetical searches from this real one is unconvincing. We are told that the “privacy-related concerns†in the search of a home “are weighty enough that the search may require a warrant, notwithstanding the diminished expectations of privacy of the arrestee.†… But why are the “privacy-related concerns†not also “weighty†when an intrusion into the body is at stake? (The Fourth Amendment lists “persons†first among the entities protected against unreasonable searches and seizures.) And could the police engage, without any suspicion of wrongdoing, in a “brief and . . . minimal†intrusion into the home of an arrestee—perhaps just peeking around the curtilage a bit? … Obviously not.

Scalia also points out another troubling aspect of the Supreme Court’s ruling is that persons shown by subsequent investigation to be innocent of the crime are the most wronged by this ruling.

The Act authorizes Maryland law enforcement authorities to collect DNA samples from “an individual who is charged with . . . a crime of violence or an attempt to commit a crime of violence; or . . . burglary or an attempt to commit burglary.” Md. Pub. Saf. Code Ann. ?2- 504(a)(3)(i) (Lexis 2011).

After explaining what Maryland defines as a serious crime the statute again clarifies when the DNA testing takes place:

Once taken, a DNA sample may not be processed or placed in a database before the individual is arraigned (unless the individual consents). Md. Pub. Saf. Code Ann.

(Arraignment is the first stage of courtroom-based legal proceedings in which charges are read; the defendant’s right to an attorney is explained; the defendant pleads (guilty, not guilty, no contest); bail is determined and court dates are set.)

Scalia writes:

All parties concede that it would have been entirely permissible, as far as the Fourth Amendment is concerned, for Maryland to take a sample of King’s DNA as a consequence of his conviction for second-degree assault. So the ironic result of the Court’s error is this: The only arrestees to whom the outcome here will ever make a difference are those who have been acquitted of the crime of arrest (so that their DNA could not have been taken upon conviction). In other words, this Act manages to burden uniquely the sole group for whom the Fourth Amendment’s protections ought to be most jealously guarded: people who are innocent of the State’s accusations. (Emphasis WWTFT)

Scalia further argues:

Today’s judgment will, to be sure, have the beneficial effect of solving more crimes; then again, so would the taking of DNA samples from anyone who flies on an airplane (surely the Transportation Security Administration needs to know the “identity†of the flying public), applies for a driver’s license, or attends a public school. Perhaps the construction of such a genetic panopticon is wise. But I doubt that the proud men who wrote the charter of our liberties would have been so eager to open their mouths for royal inspection.

What Scalia does not say but hints at is that this decision further extends the tentacles of overreaching and unaccountable government. A government that is privy, through federal law and regulation, to the most intimate details of private life.

Obama Care requires a massive database of everyone’s medical history. Core Standards mandate the collection of information on every public school child and his or her family. The IRS obviously collects everyone’s financial data and has expanded its purview into collecting political views and names of associates.

Congressional hearings document how the power to access information can be used for nefarious purposes. Hearings also revealed that government employees who reported official wrongdoing were subjected to retaliation from superiors who had something to hide.

Consider how average citizens would fare if their exercise of First Amendment rights not only jeopardized their tax status but also threatened access to appropriate medical treatment, and children’s educational and employment opportunities. Now add a national DNA database for “identification†purposes.

If these concerns seem overblown because the Constitution limits government and protects Americans’ unalienable rights, then please explain that to the Americans who found themselves on the President’s “enemies list”, to Gibson Guitar, to those who have been subjected to repeated audits and investigation. Tell that to the reporters at Fox News and the Associated Press whose personal and private communications were monitored. And don’t forget to clarify for the individuals harassed by the IRS because of their political beliefs. One has only to read the headlines to begin to get a sense of the breadth and depth of this corruption and abuse of power.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

5 comments

Your opening paragraph is exactly what I thought when I read about this decision. I almost always side with Scalia’s positions, but to also agree with Ginsberg, Kagan and Sotomayor? That required me to sit on the couch for a few minutes to collect myself. I got a little light-headed. Now, with the revelations that the NSA is collecting data on Verizon customers’ phone calls makes Scalia’s defense of the 4th Amendment all the more important.

[Reply]

“’Curiouser and curiouser!’ Cried Alice (she was so much surprised, that for the moment she quite forgot how to speak good English). ’Now I’m opening out like the largest telescope that ever was! Good-bye, feet!’ (for when she looked down at her feet they seemed to be almost out of sight, they were getting so far off).”

[Reply]

I am no legal scholar, but I would tend to agree with Scalia. Our government has so much information at its disposal, it is becoming a dangerous thing. How easy it is to collect DNA and plug it into a database, all for the common good. I call that a fishing expedition. Just like the one currently underway by the NSA as they dig into phone records at Verizon.

[Reply]

Martin Reply:

June 6th, 2013 at 5:37 pm

I don’t think you have to be a legal scholar to realize the danger here.

[Reply]

LD Jackson Reply:

June 6th, 2013 at 5:39 pm

True enough. A little common sense, applied to conservative values, goes a long way.

[Reply]

Leave a Comment