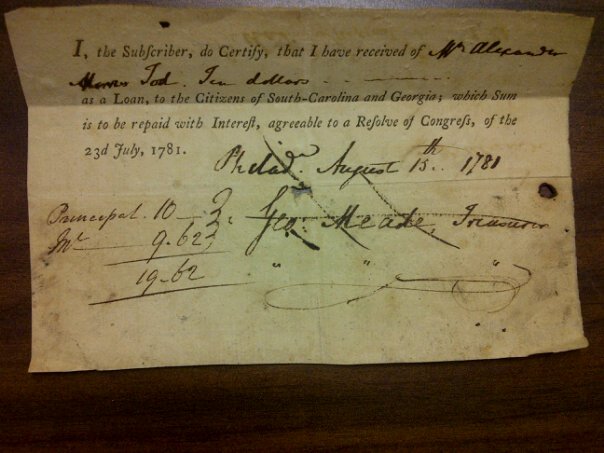

Helping Displaced Patriots: A Welfare Program From 1781

In 1781, Alexander Todd loaned $10 to help displaced Patriots in South Carolina and Georgia; this was the receipt, signed by Treasurer George Meade. Repayment of the $10 plus $9.62 in interest came in 1797 to Todd’s estate, after Todd had died, and was performed by Josiah Smith, Jr., Cashier of the Charleston branch of the Bank of the United States. The Historical Society of Pennsylvania has the “list of subscribers” to the program as donated by Civil War General George G. Meade.  Image used with permission from the South Carolina Department of Archives and History. Views expressed in this post do not necessarily represent those of the SCDAH.

By mid-1781, the British “Southern Strategy” had taken its toll on South Carolina and Georgia. Even while General Nathanael Greene was beginning to take back South Carolina for the Continentals, many civilian Patriots in the southernmost new states found themselves penniless fugitives amidst the heavy Redcoat presence. Â They had lost everything, many having fled to safety in the northern states.

But they were not forgotten or ignored. On June 23, 1781, the Congressional representatives of South Carolina and Georgia introduced a resolution to aid their fellow statesmen in need:

Resolved, That Commissioners [five suitable persons] be appointed and authorised to open a subscription for a loan of [thirty thousand] dollars, for the support of such of the citizens of the states of South Carolina and Georgia, as have been driven from their country and possessions by the enemy, the said states, respectively, by their delegates in Congress, pledging their faith for the re-payment of the sums [so lent,] with interest, [in proportion to the sums which shall be received by their respective citizens, as soon as the legislatures of the said states shall severally be in condition to make provision for so doing], and Congress hereby guaranteeing this obligation:

That the said Commissioners [five persons] do also receive voluntary and free donations, to be applied to the support of such [further relief of the said sufferers as are willing to accept the same.

Ordered, That the President send a copy of the above resolution to the executives of the several states not in the power of the enemy, requesting them to promote the success of the said loan and donation within their respective bounds in such way as they shall think best.

The resolution having passed, the commission was set up (its Treasurer would be George Meade, grandfather of the Civil War general), and many individuals began loaning and donating money to aid those in need. Â It was, in essence, a welfare scheme, but one that was very different than what we see today, emphasizing several core Founding principles:

1. Voluntary charity. In this case, those who loaned money would eventually receive it back with interest. Similarly, in our day, we can get tax deductions.  Nobody was forced to loan money for this cause, but many did, and some even flat-out donated. Americans compassionately gave when not forced to do so.

2. Capitalism. Because funds were to be repaid with interest, there was no true goal of wealth redistribution. Eventually, those South Carolinians and Georgians who received aid would, theoretically, repay the loans themselves through taxes collected at the state level. Additionally, this plan on the whole was an excellent example of the free market displaying ingenuity to entice investors, offering a solid product and promising a good return. Unlike modern entitlement programs, those who made loans under this plan in 1781 did so of their own choice, understanding the riskiness of their investments.

3. Federalism. The structure of the resolution placed the federal government in its proper role of an agent to help facilitate the process, something that would have been sloppy if handled by multiple states in the midst of a war on home soil. The oversight commission was therefore to be a federal one, but it was only to help smooth the process, ensuring that accounts were taken and streamlining the funds transfers. South Carolina and Georgia took responsibility for repaying the loans in the future, and Congress placed the burden of soliciting loaners and donors on the several states (after the President, acting once again only as a facilitating agent, sent the other states copies of the resolution).

In the end, Americans loaned and donated money in a creatively-designed system that relied on the people for charity and investment, on the states for solicitation and repayment, and on the federal government for bookkeeping. Through it all, they helped fellow countrymen who needed a hand-up through no fault of their own and who hoped to not remain impoverished forever just because the British swept through their home towns. If the British had won the war, these monies would have been lost, but then so would have most everything else in the possession of those who were Patriotic enough to have publicly made such loans in the first place. But with the Americans having prevailed, the entitlement-program-as-a-voluntary-investment idea was a winner in itself. It’s one that could serve as a model for how to truly “promote the general Welfare,” especially in these budget-crunched times.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

2 comments

Great post!

[Reply]

Craig S. Glass Reply:

March 30th, 2011 at 9:32 pm

Thanks!

[Reply]

Leave a Comment