Great Reviews

The most recent edition of the The Claremont Review of Books contains great reviews of two new books on the American founding.

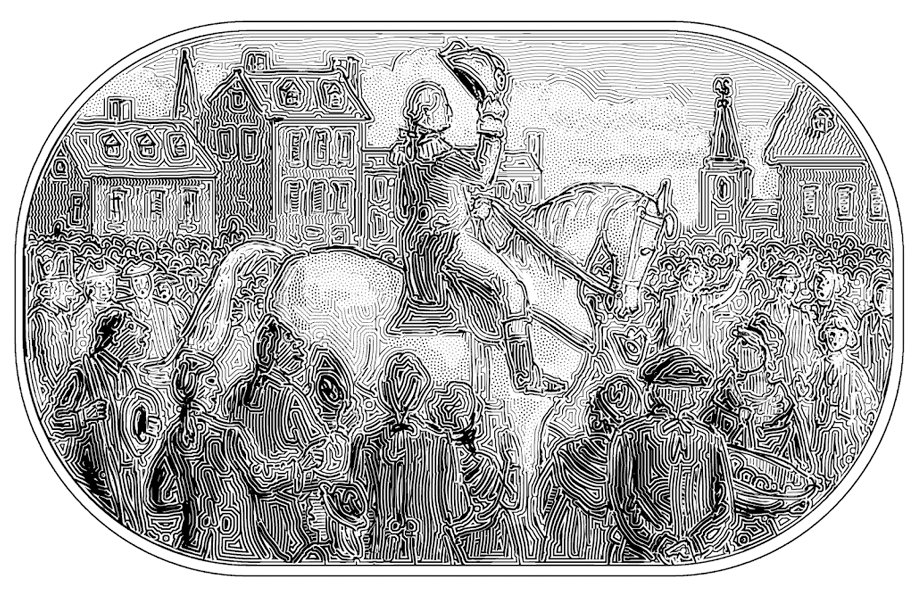

In a review entitled The First American, Robert K. Faulkner covers Robert K. Middlekauff’s Washington’s Revolution: The Making of America’s First Leader.

This reader needed no convincing about whether or not to add this book to his list. Middlekauff is a great writer and is always interesting. Faulkner’s brief (for Claremont) review focuses on Washington’s unbending determination to be honorable – even while being a shrewd and ambitious politician.

Robert Middlekauff has written a morally generous and politically shrewd account of how constitutional, revolutionary, paradoxical, and politically formative was General George Washington, even before his two terms as president.

In a review entitled Four-Horse Parlay, Michael Nelson provides not only a great summary of Joseph J. Ellis’s new book The Quartet: Orchestrating the Second American Revolution, but also adds some interesting commentary of his own.

This is not a book that will, in all likelihood, make it to the top of the WWTFT reading list. Â Ellis is a good writer, but this is ground that has been covered a lot by WWTFT reviewers – and there are literally dozens of other titles already in the queue. Â However, that isn’t to say that this is a book not worth reading. Â Nelson’s review indicates that it is – especially for those who may not have plowed this ground before.

The value of Ellis’s book, in addition to its graceful prose and sure command of the period, is that it tells this story yet again to a nation that may have heard it but still hasn’t gotten the main point, which is that the orchestrators of the long, uphill sequence of events that led to enactment—call them framers, founders, or even Founding Fathers—were, in the best sense of the word, scholar-politicians. Almost to a one, they were widely read and deeply thoughtful about political philosophy. They also were richly experienced in war, politics, and government. Of the 55 convention delegates, Ellis records, “[t]hirty-five had served as officers in the Continental Army, and forty-two had served in the Continental or Confederation Congress.†The modern distinction between academics who reflect about politics and politicians who practice it had no place among them. Politics at its best entailed both intense study of the public good and the messy, complicated process of working to achieve as much of it as possible.

Both of these reviewers did a phenomenal job – the reviews are worth reading on their own merits – especially if one lacks the time to read the books about which they were written.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!