Federalist 20

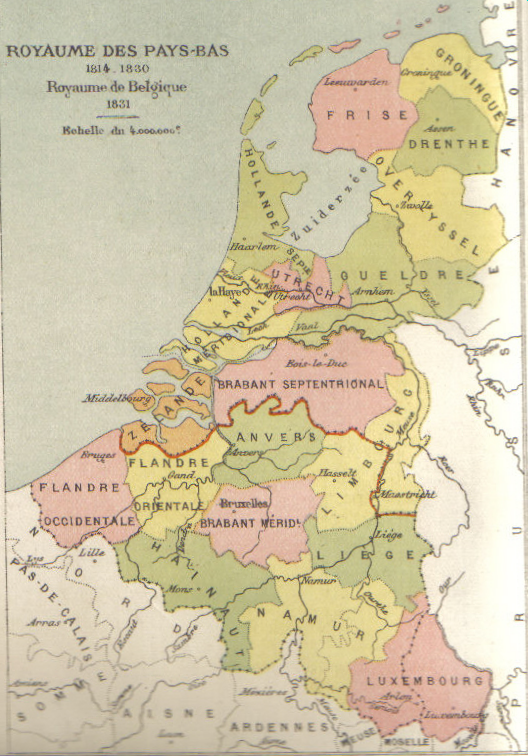

Federalist No. 20 is the last in a series of 6 essays on the “Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union.” In this essay, Hamilton and Madison collaborate (you can tell by the writing) to show the struggles of a contemporary confederacy, that of the Netherlands. According to Hamilton and Madison, despite its singularity, the United Netherlands were prone to the same problems which plagued the other confederacies covered in the preceding 5 essays.

Publius hammers his point home, suggesting that, “Experience is the oracle of truth; and where its responses are unequivocal, they ought to be conclusive and sacred.“

Their conclusion is that a confederacy of equal sovereignties cannot stand. There must be a supreme central authority for a union to function.

The Insufficiency of the Present Confederation to Preserve the Union (continued)

To the People of the State of New York:

THE United Netherlands are a confederacy of republics, or rather of aristocracies of a very remarkable texture, yet confirming all the lessons derived from those which we have already reviewed.

Although seemingly unique because of their aristocratic nature, the United Netherlands have been prone to the same issues we have documented for other confederacies.

The union is composed of seven coequal and sovereign states, and each state or province is a composition of equal and independent cities. In all important cases, not only the provinces but the cities must be unanimous.

The Netherlands’ Union is composed of seven coequal and sovereign states, and each state or province is a composition of equal and independent cities. For any significant cooperative action, not only the provinces but the cities must be unanimous.

The sovereignty of the Union is represented by the States-General, consisting usually of about fifty deputies appointed by the provinces. They hold their seats, some for life, some for six, three, and one years; from two provinces they continue in appointment during pleasure.

The Union government is represented by the States-General, consisting usually of about fifty deputies appointed by the provinces. They hold their seats, some for life, some for six, three, and one years; from two provinces they continue in appointment during pleasure.

The States-General have authority to enter into treaties and alliances; to make war and peace; to raise armies and equip fleets; to ascertain quotas and demand contributions. In all these cases, however, unanimity and the sanction of their constituents are requisite. They have authority to appoint and receive ambassadors; to execute treaties and alliances already formed; to provide for the collection of duties on imports and exports; to regulate the mint, with a saving to the provincial rights; to govern as sovereigns the dependent territories. The provinces are restrained, unless with the general consent, from entering into foreign treaties; from establishing imposts injurious to others, or charging their neighbors with higher duties than their own subjects. A council of state, a chamber of accounts, with five colleges of admiralty, aid and fortify the federal administration.

The States-General have authority to enter into treaties and alliances; to make war and peace; to raise armies and equip fleets; to ascertain quotas and demand contributions. In all these cases, however, unanimity and the sanction of their constituents are required. The Union government has the authority to appoint and receive ambassadors, to execute treaties and alliances already formed, and to provide for the collection of duties on imports and exports. It also has the power to regulate the mint, with a saving to the provincial rights and to govern the dependent territories. The provinces are prohibited, unless with the general consent, from entering into foreign treaties; from establishing imposts injurious to others, or charging their neighbors with higher duties than their own subjects. The federal administration contains a council of state, a chamber of accounts, and five colleges of admiralty, which support the federal administration.

The executive magistrate of the union is the stadtholder, who is now an hereditary prince. His principal weight and influence in the republic are derived from this independent title; from his great patrimonial estates; from his family connections with some of the chief potentates of Europe; and, more than all, perhaps, from his being stadtholder in the several provinces, as well as for the union; in which provincial quality he has the appointment of town magistrates under certain regulations, executes provincial decrees, presides when he pleases in the provincial tribunals, and has throughout the power of pardon.

A hereditary prince holds the office of executive magistrate, known as stadtholder, for the union. His power is derived from the weight and influence he wields as a result of this independent title and patrimonial estates. He also has significant family connection with some of the chief potentates of Europe. What’s more, he has the authority to appoint town magistrates, execute provincial decrees, and preside in provincial tribunals if he chooses. Finally, he also has the power of pardon throughout the provinces.

As stadtholder of the union, he has, however, considerable prerogatives.

In his political capacity he has authority to settle disputes between the provinces, when other methods fail; to assist at the deliberations of the States-General, and at their particular conferences; to give audiences to foreign ambassadors, and to keep agents for his particular affairs at foreign courts.

In his role as stadtholder of the union, he has considerable prerogatives.

Politically, he has authority to settle disputes between the provinces, when other methods fail. He assists at the deliberations of the States-General, and at their particular conferences. It is he that receives foreign ambassadors, and keeps agents for his particular affairs at foreign courts.

In his military capacity he commands the federal troops, provides for garrisons, and in general regulates military affairs; disposes of all appointments, from colonels to ensigns, and of the governments and posts of fortified towns.

Militarily, he commands the federal troops, provides for garrisons, and in general regulates military affairs. The stadthoder makes all appointments, from colonels to ensigns, and of the governments and posts of fortified towns.

In his marine capacity he is admiral-general, and superintends and directs every thing relative to naval forces and other naval affairs; presides in the admiralties in person or by proxy; appoints lieutenant-admirals and other officers; and establishes councils of war, whose sentences are not executed till he approves them.

With regard to the naval affairs, he is admiral-general, and superintends and directs every thing relative to naval forces and other naval affairs. He presides in the admiralties in person or by proxy. He appoints lieutenant-admirals and other officers; and establishes councils of war, whose sentences are not executed till he approves them.

His revenue, exclusive of his private income, amounts to three hundred thousand florins. The standing army which he commands consists of about forty thousand men.

His revenue, not including his private income, amounts to three hundred thousand florins. The standing army which he commands consists of about forty thousand men.

Such is the nature of the celebrated Belgic confederacy, as delineated on parchment. What are the characters which practice has stamped upon it? Imbecility in the government; discord among the provinces; foreign influence and indignities; a precarious existence in peace, and peculiar calamities from war.

This is how the celebrated Belgic confederacy is delineated on parchment. So, how does it work in practice? The government horribly inefficient. There is discord among the provinces. It suffers from foreign influence and indignities. Neither is it terribly stable in peace, and even less so under the peculiar calamities from war.

It was long ago remarked by Grotius, that nothing but the hatred of his countrymen to the house of Austria kept them from being ruined by the vices of their constitution.

It is as Grotius said long ago, nothing but the hatred of his countrymen to the house of Austria kept them from being ruined by the vices of their own constitution.

The union of Utrecht, says another respectable writer, reposes an authority in the States-General, seemingly sufficient to secure harmony, but the jealousy in each province renders the practice very different from the theory.

According to another respectable writer, the States General under the union of Utrecht, while seemingly sufficient to ensure harmony, fails to do so in practice, because of the jealousy in each province.

The same instrument, says another, obliges each province to levy certain contributions; but this article never could, and probably never will, be executed; because the inland provinces, who have little commerce, cannot pay an equal quota.

Another points out that although on paper, each province is supposed to contribute their fair share, this is practically impossible because the inland provinces have little commerce and cannot do so.

In matters of contribution, it is the practice to waive the articles of the constitution. The danger of delay obliges the consenting provinces to furnish their quotas, without waiting for the others; and then to obtain reimbursement from the others, by deputations, which are frequent, or otherwise, as they can. The great wealth and influence of the province of Holland enable her to effect both these purposes.

Concerning contribution to the general fund, they usually end up waiving the stipulations of the constitution for practical reasons. Since the dangers engendered by delay are great, those provinces which are able to furnish their quotas and cover the shortfalls, do so without waiting for the others. They then seek to obtain reimbursement from the others as best they can. Holland, because of its great wealth and influence is able to make its payments and then coerce repayment from the others.

It has more than once happened, that the deficiencies had to be ultimately collected at the point of the bayonet; a thing practicable, though dreadful, in a confedracy where one of the members exceeds in force all the rest, and where several of them are too small to meditate resistance; but utterly impracticable in one composed of members, several of which are equal to each other in strength and resources, and equal singly to a vigorous and persevering defense.

It has happened more than once that these defaults had to be collected at the point of bayonet. This is practical, though undesirable, in a confederacy where one of the members is stronger than the rest, and where the smaller are too small to band together to offer meaningful resistance. However, this doesn’t work at all in a confederacy composed entirely of members which are equal to each other in strength and resources, and where each are willing to defend themselves.

Foreign ministers, says Sir William Temple, who was himself a foreign minister, elude matters taken ad referendum, by tampering with the provinces and cities. In 1726, the treaty of Hanover was delayed by these means a whole year. Instances of a like nature are numerous and notorious.

According to Sir William Temple (himself a foreign minister), foreign ministers frequent elude matters by quibbling over details as they pertain to the provinces and cities. For instance, in 1726, the treaty of Hanover was delayed by such means for a whole year. This sort of thing is by no means uncommon and occurs frequently.

In critical emergencies, the States-General are often compelled to overleap their constitutional bounds. In 1688, they concluded a treaty of themselves at the risk of their heads. The treaty of Westphalia, in 1648, by which their independence was formerly and finally recognized, was concluded without the consent of Zealand. Even as recently as the last treaty of peace with Great Britain, the constitutional principle of unanimity was departed from. A weak constitution must necessarily terminate in dissolution, for want of proper powers, or the usurpation of powers requisite for the public safety. Whether the usurpation, when once begun, will stop at the salutary point, or go forward to the dangerous extreme, must depend on the contingencies of the moment. Tyranny has perhaps oftener grown out of the assumptions of power, called for, on pressing exigencies, by a defective constitution, than out of the full exercise of the largest constitutional authorities.

In critical emergencies, the States-General are often compelled to over step their constitutional bounds. In 1688, they concluded a treaty of themselves at the risk of their heads. The treaty of Westphalia, in 1648, by which their independence was formerly and finally recognized, was concluded without the consent of Zealand. Even as recently as the last treaty of peace with Great Britain, they ignored constitutional principle of unanimity. A weak constitution must always either end in dissolution, for want of proper powers, or resort to the usurpation of powers requisite for the public safety. Once begun, this usurpation may or may not end. It may go forward to the dangerous extreme. This depends on the contingencies of the moment. Tyranny perhaps most frequently arises out of the assumptions of power, out of necessity because of a defective constitution, than out of the full exercise of the largest constitutional authorities.

Notwithstanding the calamities produced by the stadtholdership, it has been supposed that without his influence in the individual provinces, the causes of anarchy manifest in the confederacy would long ago have dissolved it. “Under such a government,” says the Abbé Mably, “the Union could never have subsisted, if the provinces had not a spring within themselves, capable of quickening their tardiness, and compelling them to the same way of thinking. This spring is the stadtholder.” It is remarked by Sir William Temple, “that in the intermissions of the stadtholdership, Holland, by her riches and her authority, which drew the others into a sort of dependence, supplied the place.”

As ineffectual and problematic as it is, without the influence of the statdtholder in the individual provinces, the confederacy would long ago have dissolved into the nascent anarchy evident there. According to the Abbé Mably, “… the Union could never have subsisted, if the provinces had not a spring within themselves, capable of quickening their tardiness, and compelling them to the same way of thinking. This spring is the stadtholder.” Sir William Temple has remarked, “that in the intermissions of the stadtholdership, Holland, by her riches and her authority, which drew the others into a sort of dependence, supplied the place.”

These are not the only circumstances which have controlled the tendency to anarchy and dissolution. The surrounding powers impose an absolute necessity of union to a certain degree, at the same time that they nourish by their intrigues the constitutional vices which keep the republic in some degree always at their mercy.

These are not the only circumstances which have restrained the tendency to anarchy and dissolution. To a certain degree, the surrounding powers make union a necessity. At the same time, these powers intrigue to exploit the inherent vices in the constitution to keep the republic in some degree always at their mercy.

The true patriots have long bewailed the fatal tendency of these vices, and have made no less than four regular experiments by extraordinary assemblies, convened for the special purpose, to apply a remedy. As many times has their laudable zeal found it impossible to unite the public councils in reforming the known, the acknowledged, the fatal evils of the existing constitution. Let us pause, my fellow-citizens, for one moment, over this melancholy and monitory lesson of history; and with the tear that drops for the calamities brought on mankind by their adverse opinions and selfish passions, let our gratitude mingle an ejaculation to Heaven, for the propitious concord which has distinguished the consultations for our political happiness.

The true patriots of the republic have long bemoaned the fatal flaws of the consitution, and have tried at least four regular times to address them by extraordinary assemblies. Although well-intentioned, they have found it impossible to unite the public councils in reforming the known, the acknowledged, the fatal evils of the existing constitution. Let us pause, my fellow-citizens, for one moment, over this melancholy and monitory lesson of history. Even as we see, displayed before us, the results of selfish passions and adverse opinions in their situation, we can be grateful for the propitious concord which has distinguished our own convention and bodes well for our political happiness.

A design was also conceived of establishing a general tax to be administered by the federal authority. This also had its adversaries and failed.

Returning to the Netherlands, they were also unable to establish a general tax to be administered by the federal authority.

This unhappy people seem to be now suffering from popular convulsions, from dissensions among the states, and from the actual invasion of foreign arms, the crisis of their distiny. All nations have their eyes fixed on the awful spectacle. The first wish prompted by humanity is, that this severe trial may issue in such a revolution of their government as will establish their union, and render it the parent of tranquillity, freedom and happiness: The next, that the asylum under which, we trust, the enjoyment of these blessings will speedily be secured in this country, may receive and console them for the catastrophe of their own.

The result of all this, is that these unhappy people now suffer from popular unrest, dissension among the states, and from the actual invasion of foreign arms. Their very future is imperilled. All nations have their eyes fixed on the awful spectacle. Common humanity impels us to hope that some kind of revolution of their government will establish their union, and provide tranquillity, freedom and happiness. Similarly, we hope that in this country, where we have an opportunity to avoid a catastrophe of our own, we may speedily rectify our issues.

I make no apology for having dwelt so long on the contemplation of these federal precedents. Experience is the oracle of truth; and where its responses are unequivocal, they ought to be conclusive and sacred. The important truth, which it unequivocally pronounces in the present case, is that a sovereignty over sovereigns, a government over governments, a legislation for communities, as contradistinguished from individuals, as it is a solecism in theory, so in practice it is subversive of the order and ends of civil polity, by substituting violence in place of law, or the destructive coercion of the sword in place of the mild and salutary coercion of the magistracy.

I make no apology for having focused so long on the study of these federal precedents. Experience is the oracle of truth; and where its responses are unequivocal, they ought to be conclusive and sacred. The important truth, unequivocally obvious in the case of the Netherlands, is that a sovereignty over sovereigns, a government over governments, a legislation for communities, cannot be compared with that for individuals. The concept is an error in theory, which in practice destroys the goal civil polity, by substituting violence in place of law, or the destructive coercion of the sword in place of the mild and salutary coercion of the magistracy.

PUBLIUS

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

0 comments

Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment