Designing A Polity, America’s Constitution in Theory and Practice By James W. Ceaser

James W. Ceaser is a professor at the University of Virginia and the author of an impressive array of books on the American political system. Designing a Polity is the first this reviewer has read. It won’t be the last.

James W. Ceaser is a professor at the University of Virginia and the author of an impressive array of books on the American political system. Designing a Polity is the first this reviewer has read. It won’t be the last.

A polity is “How a society is arranged or shaped with a view to who governs and how power is allocated, for what basic purposes, and to generate what general way of life.â€Â The nine essays in this book discuss all of the above and more.

The author examines the foundational ideas on which constitutional government is built and argues for their continued relevance. A political foundation, as the author explains, is the central idea or set of ideas that are shared by a political community. It is a general understanding of right or good and of the source from which that understanding comes.

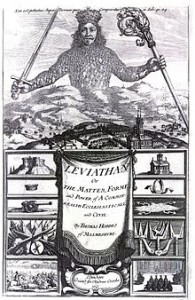

As the title promises, Ceaser explores American political philosophy and its practical applications. He examines the Constitution and the issues that roiled the anti-Federalists during the ratification debates, and that roil us still. His guides are Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, the Federalist papers, and Tocqueville. One could not ask for better.

Alexander Hamilton |

Alexis DeTocqueville |

James Madison |

Readers learn that the separation of powers and the checks and balances built into the Constitution are more nuanced than is popularly thought. For example, the three branches (Executive, Legislative and Judicial) are described in the abstract, but the Founders never explained how their powers were to be distributed in a real government. In Federalist 47 Madison writes, “The accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands, whether of one, a few, or many, and whether hereditary, self appointed, or elective, may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny.â€Â However, he goes on to add that the constitutions of the several States show “not a single instance in which the several departments of power have been kept absolutely separate and distinct.â€Â Madison asserts the “impossibility and inexpediency†of a strict separation.

The limits of presidential power divided Federalists and anti-Federalists. Anti-Federalists generally favored a more limited role. According to one view, the executive would be confined to its ministerial function of carrying out legislative enactments. The Founders had a broader vision. Although they wanted checks on executive power, they were determined to reverse the weakness of the Articles of Confederation. The president had to be able to respond to crises as they arose, to conduct foreign policy and to exert leadership for his administration. The limits of that power remain in contention.

Ceaser discusses the current challenge to the Constitution by Progressives and identifies their antecedents in political nonfoundationalism. Nonfoundationalism denies that objective truth exists and finds such notions as “a transcendent law of nature and nature’s god†archaic and anti-democratic.

Political nonfoundationalism has been widely accepted by the intellectual class in America, which now considers it to be virtually a self-evident truth. Nonfoundationalism appeals to this class’s belief in the dogma of theoretical relativism while offering simultaneous assurances that nothing in this position endangers the promotion of the same class’s cherished progressive values.

It is not only the religious foundation that they reject; it is any theoretical foundation at all. To elaborate the author quotes Shelby Steele:

America was a foundational nation, but we were hypocritical … Many people argued that foundational principles were really a pretext for evil, out of which came the darker evil—the west—that dominated the world and oppressed people.

Nonfoundationalsim sees itself as morally superior. Or in Steele’s words,

They are saying we’re not partaking of the hypocrisy and we’ve got new things like diversity and tolerance that don’t have any foundational basis and aren’t grounded in principle. They’re just grounded in wonderfulness.

Ceaser points out that contrary to its claims, nonfoundationalism is unable to support liberal democracy. He writes:

Nonfoundationalism creates a vacuum in the public realm with regard to the truth of first principles. It claims, with no experience to prove it, that a polity of this kind will be stable. But is not the circumstance of an empty public square the most fertile soil in which holistic political religions and ideologies are most likely to take hold? Did not the destruction of real religion among the elites of France in the eighteenth century prepare the way for the creation of the political religion of the Revolution, in much the same fashion as the promotion of nihilism in the early part of the twentieth century helped prepare the way for Fascism and Communism?

The publication of Designing a Polity comes at a time of renewed interest in the founding; an interest sparked in no small measure by the left’s effort to undermine the Constitution and its foundational principles. Or as the author observes, “It has been said that the conservative movement in America today is held together by two self-evident truths: Barack Obama and Nancy Pelosi.â€

With that introductory aside, Ceaser examines the branches of American conservatism, their differences, and the values they share.

He concludes the book with an exposition on anti-Americanism, which he calls the only full-scale ideology with a world-wide reach. As the advanced nations of the West have increasingly adopted the new doctrine of nonfoundationalism, America, with its stubborn insistence on “a transcendent law of nature and nature’s god,†is seen as the major impediment to a new and improved world order.

This book is for anyone with an interest in better understanding the American polity, and the forces that threaten it. The author explains the nature of those forces:

Nonfoundationalism, which demands public neutrality concerning faith and non-belief, aims at a profound alteration of the character of the polity…Without a foundational principle—without the moral energy that derives from efforts to establish foundational principles—a community ceases to exist in a deep or meaningful sense, and without this energy, a nation will be unable to extract the added measure of devotion and resolve from its members that is needed to undertake important projects and to assure its survival… Western civilization today confronts two great challenges: saving itself from a new barbarism that aims to destroy it and sustaining the faith that helped to give it birth.

Designing a Polity is not an easy book to review. The scope of the essays and Ceaser’s erudition and penetrating insights cannot be described in any meaningful way in a few summative sentences. That having been said, this reviewer hopes, at least, to have conveyed the breadth of the author’s thinking, his passion for his subject, and to have produced a desire to read more James W. Ceaser.

The posts are coming!

The posts are coming!

2 comments

Thanks for finding and reviewing this book. I added it to my wish list.

[Reply]

You will find it immensely rewarding. I will be rereading it. It is a book that keeps on giving.

[Reply]

Leave a Comment